Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

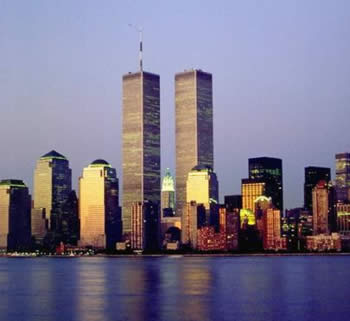

The Twin Towers

By Elaine Rosenberg Miller

The summer I was twenty, I worked in the offices of the Pipefitters and Steamfitters Union,

one of the trades constructing the twin towers of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

The ceiling tiles in the room in which I sat had not yet been installed and one morning, a

black fleck of asbestos floated down and landed in my eye. It felt as if a pin had embedded

itself in the soft, white cornea. Somehow, three subway trains and a bus later, I made it back

home. The next day, an ophthalmologist pinned my head in a vise-like instrument and

removed the metal fiber with tweezers.

Each day I would walk through the dark, multi-storied lobby of one of the unfinished towers,

under meandering rectangular air ducts wrapped in blankets of aluminum colored insulation,

across the gray concrete floor lit by swinging suspended light bulbs and ponder the enormity

of the buildings.

They were to be the tallest buildings in the world. I felt proprietary towards them. Privately,

I found their windows too narrow and the outdoor plaza, uninviting. I did not know then that

additional structures, of varying heights, with warm, bronzed facades would be built and that

the towers' stark modernity would be modified as they sat in the center of an iconic complex.

My cousin worked at a nearby building. Filled with youthful ambition, we would sit on the

edge of the circular fountain between the towers as the brisk wind blew around us, eat our

lunches and daydream. She was going to be a scientist. I was going to be a writer. She,

being the better typist, re-typed my short stories until there were enough to fill a thick binder.

Our futures were boundary less, like the towers.

A few years later, after a winter of severe snowstorms, I left New York to join my new

husband in his hometown in Florida. New York had become cold, dirty, and unwelcoming.

Newspapers were filled with reports of economic recession and crime. Walking past the

stone lions guarding the Forty-Second Street Library, one could be jeered at or panhandled.

Bryant Park, adjoining the library, was a forbidden zone of wild-eyed people.

I would return to New York for visits. Gradually, New York became cleaner, safer and even

thrilling. I visited the Library again with my children. We marveled at its majestic interior. The

park was filled with flowers and people, some pushing baby strollers. How had this

happened? We took ferry rides, rode the subways, visited museums. The children would

come to know the collections at the Metropolitan Museum well. "Look at these Chaldean

rings!" I would say. "They were on the hands of a woman or man thousands of years ago.

Look at this Mediterranean wall painting. Look at the man's black, arched eyebrows. They

look like Dad's. Maybe it was his ancestor! Look at these sculptures. That's what Julius

Caesar looked like!" My elder children later attended New York colleges and began to

discover Manhattan on their own. Their friends were from Hong Kong, Berlin and Buenos

Aires. Together they attended theaters and events, ate at restaurants and clubs.

I loved to sweep down the Henry Hudson Parkway heading south from the George

Washington Bridge. The rising fog of the early morning sunrise, the cooling evening breeze,

the twinkling lights strung across the bridge, the massive apartment houses along Riverside

Drive, welcomed me back.

The appeal of New York, I decided, was its message. Anything was possible.

Achievement. Wealth. Happiness.

I rediscovered the Wall Street area. One spring Sunday, my children and I drove through

the nearly empty streets in our rental car. I craned my neck. I was aware that I looked like

a tourist. "Look! That's where I used to work. The World Trade Center. Look at those

buildings!" We parked the car in an underground parking garage and walked outside, passing

a chain link fence surrounding a construction site. "Look, they're still building things!" I said.

We visited a new museum located on the tip of Manhattan. In one of the galleries, a Nazi flag

hung against a wall. Its colors were as vibrant as if it had been dyed the previous day.

We exited outside the museum. The twin towers loomed above us, friendly, despite their

size. We passed apartment houses recently built alongside the Hudson's pebbly shore.

Horizontal, red, tubular bars bisected their tall windows overlooking the passing ships, the

Statue of Liberty and the restless river. The framing, I thought, must be there to prevent

people from falling as they watched the harbor, mesmerized by the view.

On an adjoining waterside plot of land, a skeletal wooden playground structure,

resembling a hull rose jauntily. The children climbed it. The wind increased and whipped the

waves. "These people are the luckiest in the world!" I said. "Look at that view! They can live

here and see the boats everyday and walk to work. Do you realize that these waters held

every immigrant ship coming to New York from the Dutch to the Russians fleeing the Czar?"

Sometimes, I went on and on trying to imprint a sense of history on the children and create a

place for them within it. New York, I realized, invokes that feeling. I told them of my working

at the twin towers and of my cousin typing my manuscripts and the asbestos sliver. I

stopped before their expressions became glazed.

The next day we visited Liberty Science Center in Jersey City. Long necked birds gingerly

stepped in the newly growing marshes rescued from industrial decay. We ate our

sandwiches in the outdoor seating area. I stared at the towers visible across the Hudson. I

positioned my children so that my photographs would capture the buildings. They were so

beautiful.

My younger son stepped outside his dormitory and watched the towers burn. People,

covered in ash, ran towards him. Authorities prevented him from re-entering and he was

evacuated. He called home at 9:30 a.m. and left a message stating that he was safe.

There it was on television.

Masses were running alongside the same chain link fence we had passed on that sunny

day three months ago, pillars of death following them. It resembled the scene of an old black

and white movie in which prehistoric people were depicted as trying to outrun a rapidly flowing

lava field.

As the day wore on, my eldest son failed to call, but I remained unalarmed musing that

he was far from the towers, residing several miles distant at a religious school.

My mother called and asked if I had heard from them. "He must have gone down there to

help, he has that card," she said in her heavily accented voice.

My father took the phone. He, who was so usually so strong and logical, was angry. "If he

went there," he threatened.

They, who had lost so much, through war and death, were unwilling to lose any more.

"He didn't go," I assured them. He was licensed as an emergency medical technician but

he was inexperienced and far from the scene.

Hours of calling his cell phone were unsuccessful. By nightfall, I had gotten through to a

brother of a friend, then a friend. "Do you think he went down there?" I asked. No one knew.

By 8:00 p.m., his friend called and told me that someone had told him that my son had

approached a policeman, identified himself as an EMT and caught a ride downtown in an

ambulance. "That's okay," I found myself saying. "He's a grown man. He can handle himself.

If he can help, he should be there."

He called at 10:00 p.m.

"Mom, you wouldn't believe it," he said.

The next day, he returned to the site.

"There's no one to rescue," he said.

The images continued to burn on the screen, smoking rubble, billowing clouds lifting the

souls of the defenseless dead to the heavens. My eyes filled with tears as they had so many

years past and, once again, I could not, despite my best efforts, remove the object.

~~~~~~~

from the September-October 2007 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|