|

Annals of a Traveller

By Jay Levinson

Jerusalem's Bikur Holim Hospital dates back to a very unsuitable residential building in the Old City in 1826 and the aliya several years before of the students of the Vilna Gaon. The small handful of Jewish residents had begun to grow, and there had to be some kind of organized medical care. The hospital struggled along. By 1843 Bikur Holim consisted of three rooms for patients --- not exactly enough to serve even a very small community.

The yishuv was hard-pressed for funds. Sir Moses Montefiore deserves special mention. He donated large quantities of medicines for use by those being treated.

In 1854 a building was purchased for Bikur Holim, but within ten years it became obsolete. It, as well, was too small as more and more Jews began to filter into Jerusalem, and the city started to expand outside the walls. The next solution came in 1864, when a courtyard with two not very large buildings was purchased; the buildings were for medical treatment, a pharmacy, a hospice for the terminally ill and administrative offices. The opening of the "new and enlarged" hospital came none too soon. In 1866 the facility treated a much larger number of patients after the outbreak of cholera in Jerusalem.

Over the years Bikur Holim, "the Ashkenazi Perushim Hospital," was a favorite charity of Montefiore. In his diary he described the facility as it was in 1875. The general ward consisted of two rooms, each with eight beds. One room was reserved for men, and the other was restricted to women.

As years passed, the hospital went from one financial crisis to another, but medicine never stopped. Annual financial reports were made public (and the hospital was praised for proper accounting). Administration was streamlined. And the sick continued to be treated. In 1893, for example, 781 patients were hospitalized, and 12,347 people were treated as out-patients.

By 1907 Jerusalem was a different city than it had been in years past. The Jewish population had increased dramatically, and new neighborhoods took root outside the city walls. Medicine had changed. The old Bikur Holim no longer served the city as it had in the past. Hospitalizations exceeded 1000 per annum. A decision was taken to build a new hospital in New Jerusalem. Residents of the Old City were afraid of the change, but endorsement of the move by Rabbis of the time --- Berlin, Salant, Sonnenfeld, Kook --- muted opposition.

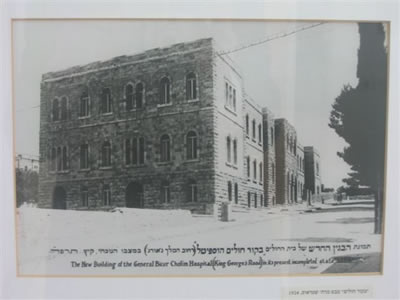

The New Bikur Cholim Hospital on King George (Strauss) Street

photo courtesy of Bikur Cholim Hospital

The cornerstone of the new building was laid in 1912, but with the outbreak of the "Great War" two years late, construction was halted until after Ottoman surrender in Jerusalem and the general Armistice in 1918. The pressure to build, however, was unabated. By 1913 there were more than 65,000 outpatients treated by Bikur Holim, five times as many as twenty years previous.

Times were changing. The Ottoman Empire had fallen. The British took over. There were Arab riots. Construction on the new Bikur Holim building was slow, but by 1925 it was finished. Bikur Holim, a modern hospital for all of the city's residents --- Jews and non-Jews alike --- opened on Chancellor Avenue (now Rechov Strauss) just off Jaffa Road. (The hospital in the Old City was not closed. It was used to treat the chronically ill until 1947, when British troops helped transfer the besieged sick to the no longer so-new -hospital.)

The history of the hospital during the next two decades was, in many ways, a microcosm of life during the Mandate. Many of the wounded from the Arab riots of 1929 and 1936 were brought to Bikur Holim. Wounded Jewish underground fighters were hospitalized with ruses in record keeping, so that the Mandate police could not discover their true identities and affiliation.

During the fighting of 1948 the hospital came under artillery fire from Jordanian guns. The halls of the hospital were crowded with the wounded. Haddasah / Mount Scopus was evacuated, and many of the patients were transferred to Bikur Holim. But, the hospital was entering a new stage of its history. It was a major medical facility just off the downtown area of the new Israeli capital.

Today Bikur Holim is one of the four religious hospitals in Israel. The guiding halachic authority is the Eida Chareidit, for all matters from kashrut to medical questions of Jewish Law; Rabbis of the Eida are consulted regularly.

In many ways the hospital is unique. Situated near the religious neighborhoods of Geula and Mea Shearim, the hospital admits a very high percentage of ultra-Orthodox Jews and tries to cater to their needs. One of the major advantages for local residents is the ability to walk to the hospital on the Sabbath, either for medical care or to visit a patient.

Shabbat is observed with exactness. Non-Jews are tasked with writing medical information and answering telephones on the Sabbath. Food is warmed usually by placing portions in an oven operated by a timer, this according to a p'sak halacha (rabbinic decision) of the Orthodox Rabbinical Courts of the Eida HaCharadit that allows the procedure for both patients and attending staff.

One specialty of Bikur Holim is the Fertility Department. Having children is a cherished Jewish value, and it is particularly important in the religious community. For that reason Bikur Holim has made major efforts in this area. Virtually all hospitals deal with female fertility and the problems of conception. Bikur Holim is one of only three hospitals in the country (and the only religiously observant hospital operating under halachic supervision) to deal with problems of male fertility.

Some males have fertility problems because of injury to the spinal column or other physical or psychological reasons. Dr. Yedidia Hovav, an observant Jew and head of the unit, explains the problem in layman's terms, "To move your hand, the brain sends a message. … Sometimes an electric stimulation is needed to help initiate the physical movement." Bikur Holim uses a similar technique of emplacing a device under anesthesia to help overcome certain male problems. Case histories have shown that the procedure is quite successful. The reader can rest assured that in each and every case, even at the patient-doctor consultation stage, Dr. Hovav works together with respected rabbinic authorities.

In their day the late Rabbis Fischer and Halberstam were frequent visitors to Bikur Holim. Today Rabbi Bransdorfer and now Rabbi Weiss are often consulted on halachic matters. The electric stimulation treatment has the explicit permission of halachic authorities, but there is no blanket approval. Each case is examined individually, and as hospital Rabbi Aharon Ros explains, stimulation is only authorized after the couple has been married for several years and has failed to bear children. Rabbi Ros, the son of an eminent rabbi who served refugees in Munich after World War II, studied for many years in the Slobodka and Brisk Yeshivos in Israel; he has s'micha from Rabbi Shmuel HaLevi Wosner and Rabbi Halberstam zt"l, and he is considered an halachic authority in his own right.

Yes, this stimulation procedure does exist abroad, but foreign patients still come to Bikur Holim even from North America and Western Europe, since they want the confidence that treatment is according to halacha. A typical stay in country is about two weeks, including both pre- and post-procedure examination.

Other problems require other solutions, some much more restricted by halachic authorities, yet permitted when deemed appropriate. In this regard, Rabbi Ros does sound one word of advice. Because of the importance of the mitzvah of bearing children, even the most highly respected rabbis are more lenient in permitting procedures than is commonly thought. It is best to ask a serious halachic question rather than presuming that something is always forbidden.

Sometimes rabbis permit it; sometimes they do not. Rabbi Elyashiv, for example, has permitted special procedures for a first child, but he is much more reluctant if a couple already has children.

Discretion and respect for privacy preclude citing examples and details mentioned by Bikur Holim representatives. What is perhaps most important is to know that these services are not only available, but they are offered within a strict halachic context. The hospital is also not averse to listening to the input of the patient's personal rabbi.

~~~~~~~

from theMay 2008 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|