Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

My Trusted Teacher, Mr. Fischer

By Renate G. Justin

Mr. Fischer was a good teacher. As an eight year old I admired him, could find no fault with him. During my second year in school he taught me mathematics, singing and showed me how to write the steep, pointed German script. School was fun in 1933 in the small German village where I lived. My friends, my neighbors, and I walked to school at seven in the morning singing and laughing; when we skipped our braids would swing from side to side. On our backs we carried a leather satchel which contained our books. A smaller leather pouch hung around our necks, in it we had our lunch, a liverwurst sandwich on dark bread and an apple out of our garden. Our classroom was large with white washed walls and tall windows which looked out on the yard where we spent recess.

We sat on long, wooden benches, fifteen to twenty per bench, with inkwells and pens on the writing extension. There were ninety students in our class. Mr. Fischer was strict, but rewarded us for good work by reading a story about German heroes, inventors, poets or painters. He often praised me for paying attention and bringing neat homework in on time.

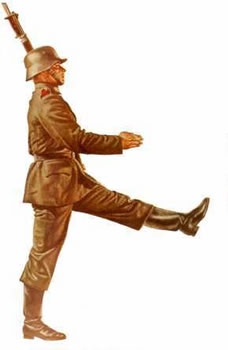

We had six weeks of vacation in the summer. It was during my vacation, I was walking to the store to do an errand for my mother, when I met my teacher, Mr. Fischer. I noticed that he had grown a mustache and was wearing a brown uniform, at that time still unfamiliar to me, with a brown military cap and swastika band on his arm. He was tall and his knee-high boots made him look even taller. I greeted him joyfully, glad to see him, "Guten Morgen, Herr Fischer." To my mortification he did not look at me, but walked past me with long strides as if I did not exist. No greeting, no acknowledgement, nothing. I was hurt, puzzled at my respected teacher's behavior and told my parents about what I had experienced when I returned home.

They both were silent for an unusually long time when I finished my tale. Then my father cleared his throat, and in a serious tone said, "That is the Nazi uniform, I am surprised Mr. Fischer is wearing it already."

"What are Nazis?"

"They are people who have joined a party which abhors Jews, Seventh Day Adventists and members of other religions."

I asked, "So you think he didn't greet me because I am a Jew?"

My parents answered in unison, "Yes."

When I was nine I tried to understand what they had said, only my first, of many later attempts, to fathom this dislike, this hatred.

School started again about a week after this incidence. A new daily ceremony had been instituted. Each morning the students had to stand in the courtyard, around a flag pole with a Nazi flag, sing the Horst Wessel Nazi song while raising their right hand in the Hitler salute. I did not like this because I did not believe in the Nazi doctrine. My parents had taught me to respect the faith of others. That children deserved to be ignored, hated merely because of their religion did not make sense to me. As the only Jew in the crowd, I felt afraid, too afraid not to raise my hand. In class Mr. Fischer seemed unchanged, except that I noticed, after a few days, that he never called on me any more. Even when my hand was the only one raised, he would ignore me and go on with the lesson as if he had not noticed my effort to answer his question. Eventually I stopped raising my hand in order to avoid this continuing rejection.

Then one day my teacher called me to the front of the room where he sat. This meant my whole row of classmates had to get up to let me out of my seat, which was in the middle of the bench. While they stood in the aisle I walked up front apprehensively. Usually when Mr. Fischer called someone it meant he had observed a student whispering or not paying attention or needing discipline for some other transgression. I was unaware of any unacceptable behavior on my part. It had happened once in the past that Mr. Fischer had called me up front to the blackboard to praise me for solving a mathematics long division problem correctly. This time I had been ignored in mathematics class so I could not imagine that he would praise me for anything.

My fear increased when I noticed Mr. Fisher's face, with the angles of his mouth drawn down, his forehead wrinkled, I interpreted his expression as one of disgust, may be even hatred. I had never seen anything but kindness on his face in the past. When I reached his chair he turned me so that my back was to the class, grasped my skirt and stretched it tightly, then struck me hard three times. His thin, flexible stick made a swishing sound as it traversed the air before it reached my flesh. It hurt. Why did I deserve this? Mr. Fischer uttered not a word of explanation. I did not want to cry, but silent tears ran down my cheeks as I returned to my seat. I felt humiliated.

When I arrived home I did not tell my mother what had happened in class. I was still trying to understand why I had been punished. What had I done, or not done, that caused this to happen? My mother, however, noticed my crumpled handkerchief, my tear stained face. "How was school today?" she asked. I spilled out the whole story. When my father came home from work he had a long talk with my mother. I did not go to school the next day. My parents decided it was too dangerous, considering Mr. Fischer's Nazi party affiliation. Soon after, my mother and father sent me out of the country, across the German border, to pursue my schooling in a safer place. Alone, I had to travel to a place where I knew no one, leave my friends, my family and my home. Mr. Fischer continued to teach elementary school in the village where I once lived, in Germany.

~~~~~~~

from the November 2008 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|