|

Wooden Matzevot

By Tomek Wisniewski

Tens of thousands of the most beautiful stone tombstones managed to survive in Poland,

but not one single wooden one has been preserved.

With a few exceptions, small-town Jewish cemeteries in Poland 'exist' only on old maps and old photographs. Their rich artistic heritage has been lost, or survives only in fragmentary or merely symbolic form, e.g. walled cemeteries behind whose walls practically nothing is to be found. The most interesting and impressive tombstones (matzevot) have disappeared. They all met the same fate. The Germans used them to cobble roads and pavements, to reinforce escarpments and clad the beds and banks of rivers. They were used in the construction of flights of stairs and farmers used them as sandstone knife-sharpeners. Despite these years of destruction, tens of thousands of the most beautiful stone tombstones managed to survive in Poland, but not one single wooden one has been preserved.

For centuries the Jews erected wooden tombstones. Typically they were to be found in the poorest communities in areas where stone was in short supply. The markers of graves of the Jewish poor took the form of ordinary planks of wood painted with a simple, short dedication (Figs. 1-5). For the slightly better-off, the name and possibly surname of the deceased would be carved into the wood in Hebrew characters.

Figures 1 &2 Druzhkopola Dru¿kopol - 1916

Figure 3 Kisielin - 1917

Figure 4 Lokache £okacze - 1915

The Jews of Polesie and the area around Piñsk (nowadays Belarus but part of Poland up to 1939) grew up in a landscape dominated by wood and water. They lived in wooden cottages and worshipped in wooden synagogues – for them wooden tombstones were part of a centuries-old tradition. Wooden tombstones were also used in Volhynia, Mazowsze and Wielkopolska and by the poorest Jews in larger towns such as Bia³ystok, Wilno and Lublin. During the First World War wooden tombstones were often erected on the graves of Jewish soldiers of the Austrian army, especially in the Beskid Niski region. During the First World War several hundred wooden Jewish tombstones in the old cemetery in Lublin (founded in 1541) were also used by Russian soldiers for firewood.

The oldest wooden tombstones in Poland date from the XVIII century and come from Miejsce in the vicinity of Namys³ów. According to Marcin Wodziñski, the Jewish cemetery in Miejsce was already in existence by 1771 (www.jewishgen.org/cemetery/e-europe/pol-m.html). This date has been arrived at from

photographs

of four wooden tombstones from 1771 – 1805 from the Jewish cemetery in Miejsce. These photographs can be found in the collection of the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt-am-Main (www.kirkuty.xip.pl/miejsce.htm). The oldest of them has carved on it an inscription that reads: "Here lies a brave and honorable woman, Mrs. Chajosen, daughter of the venerable Mr. Alexander, of blessed memory. She died on Tuesday, the fifth day of Adar in the year 5531" (19 February 1771)." As a matter of fact, these photographs are one of the few traces of evidence for the existence of wooden Jewish tombstones. Archives in Poland and abroad contain only very small iconographic

collections

of Jewish necropolises from before 1939. In the course of many years of research, I (T.W.) have managed to acquire several original photographs or

postcards

of wooden tombstones pre-1939 from Ozdziutycze, £okacze, Dru¿kopol and Kisielin in Volhynia, as well as of wooden ohels with

inscriptions

from Piñsk in Polesie and from Wi³komierz in Lithuania, and just one photograph from Radom, dated 1941, of a wooden matsevah in the ghetto. Discussion here, however, will be focused on the wooden tombstones.

Figure 6 Pinsk Piñsk – 1918

Fig. 7 Wilkomir Wi³komierz

Wooden Jewish tombstones – apart from wooden funerary shrines (ohels) [Figures 6 and 7] – were usually tall and after some years had passed and the wood had begun to rot, the lower part would be cut off and the tombstone buried deeper in the ground. An identical tradition reigned in Christian cemeteries where, a few dozen years after they had been erected, the tall wooden crosses that stood there would have the rotting bottom part periodically cut off. Sometimes, after a year or two, a wooden tombstone would be removed and replaced by a stone one. In such instances – just as in the Christian tradition – the wooden tombstone served as a temporary grave marker. Members of the Burial Society, the Khevra Kadisha, were responsible for making sure that registrations were carried out properly and the necessary taxes paid.

Surviving photographs show that wooden tombstones are very similar to each other, being made from long slender wooden planks of oak or pine whose shape is vaguely reminiscent of a primitive human form. The top resembles a head and the remainder offers just the suggestion of the human body. The slender, elongated, wooden tombstone is unique in shape, in minimalist ornamentation and, especially, in the manner of accommodating the inscription to the narrow register. Although association with the human form may be unintentional, the minimalist ornamentation and accommodation of inscription to the narrow register are clearly deliberate.

Fig. 9 Kisielin

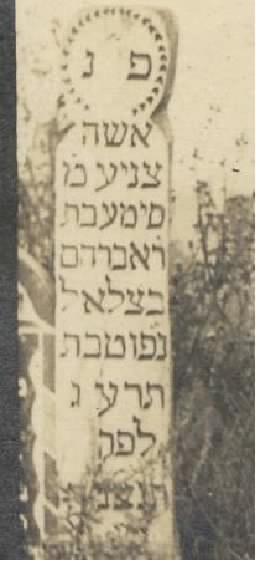

Ornamentation is absent save the simple painted or chiseled strokes that encircle the abbreviation 'Peh Nun' "Here lies" on the 'head' of the tombstones (Fig. 8). The 'head' shaped top may have been designed more to accommodate this opening abbreviation than to intentionally suggest the human form, in keeping with Jews law of aniconography (Exod. 20:3). Within inscriptions, words and abbreviations are modified in a number of ways in order to accommodate the narrow register. Such practices are generally not indicative of the Hebrew language. For example, in the opening words of the inscription from Kisielin (Fig. 9, left) - "Here lies a proper woman, Sarah Leah", the adjective 'koshrah' is simply abbreviated to the letter k' – with a vertical stroke to indicate an abbreviated word. The phrase 'a proper woman' now neatly fits the narrow register, while still offering an attribute for the deceased. In another example, this time from £okacze (Fig. 8), the attribute 'modest' 'tseniyah' [a misspelling of tsenu'ah] for the deceased woman, Sima, is truncated – the final letter Heh /h/ is simply not cut into the wood, in order to fit the phrase "modest [woman], married" into the narrow register. In yet another example, from the Jewish cemetery at Ozdziutycze (Fig. 10), the year of death is uniquely subdivided to fit the narrow register. In line five, 'year [5]6' is engraved, with the remainder of the year '71 as the abbreviated era' continuing in line six. Such subdivision has only been attested (at least by this scholar –H.S.) on granite and sandstone tombstones when the date is part of the upper register ornamentation.

Fig. 10 Ozdziutycze

Fig. 8 £okacze

The narrowness of the register also results in varied spacing or lack of spacing between words. Variation in spacing may be required by the size of the register, but it may also be a silent witness to a non-Jewish engraver unfamiliar with the conventions of the Hebrew language. Consider the tombstone inscription of Sima daughter of R. Abraham in Figure 8 (enlarged from Fig. 4 £okacze). At times, each individual word is discernable by a slight but adequate spacing, as depicted in line 1 between "Sima" and the abbreviation for 'married or Mrs.' (Mem with dot above). In line 3 of Sima's inscription, there is an even smaller separation between the words "Sima" and "daughter of". In line 4, the abbreviation for Reb (Resh with dot above) conjoins the proper name Abraham. Similarly, in line 6, in the phrase: "She died 6 Tevet", the letter zayin (for number 6) is conjoined to the abbreviation for 'she died' (Nun Peh with dot above), whereas the month 'Tevet' preserves an almost minimal word separation from the preceding zayin. By contrast, line 7, which preserves the year of death – [5]673, maintains a uniform juxtaposition of the letters representing [5]67, but the gimel (number 3) is disproportionately separated to 'fill out' the register. In line 8, Lamedh-Peh-Qoph, the abbreviation for "as the abbreviated era", is neither centered nor stretched to accommodate the space available. Whereas the closing abbreviation – Tav-Nun-Tzadeh-Bet-Heh "May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life", is nicely centered with each letter in appropriate juxtaposition.

Like the XVIII century wooden tombstone from Miejsce (described above), the legible inscriptions from wooden tombstones on the photographs from Kisielin, £okacze and Ozdziutycze are equally brief in their epithets for the deceased. These three photographs preserve fifteen legible and nearly complete inscriptions, one dating to 1895, with the remaining tombstones from 1904-1913. Two complete and one partial inscriptions are legible from Kisielin (left to right):

'Here lies a proper woman, the married Sarah Leah daughter of [remainder not visible]"

Here lies a modest woman, MAL(?) daughter of R. Meir. Died 15th(?) Cheshvan Year 5664 (1904) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a perfect man the late/married Dov Meir son of Yehudah. Died 8th(?) Iyar year 5655 (1895) as the abbreviated era. [May his soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life]."

Six nearly complete and legible inscriptions are evidenced in the £okacze photograph (left to right):

"Here lies a modest woman, the married Sima daughter of R. Abraham Becalel. She died 7th Tevet 5673 (1913) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a married woman, Rivkeh Leah daughter of R. [---el]. She died 1st Tishri 5672 (1912) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a perfect and upright man, the late/married Jehudah son of R. Jakob. He died 29th Elul 5669 (1909) as the abbreviated era. May his soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a modest woman, the married Rivkeh Leah, daughter of Jehudah Lejb. She died 21 days to the month of [---] year [56]6(?)9 (1909). May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a woman, the married Sarah daughter of R. Jakob [remainder not visible]."

"Here lies a woman, the married Chana daughter of R. Cwi. She died 3rd Kislev 5670 (1910) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound [in the bond of everlasting life]."

"Here lies a perfect and upright man, the late/married [remainder not visible].

Seven nearly complete and legible inscriptions are preserved in the Ozdziutycze photograph (left to right):

"Here lies a modest woman, the married Berkah(?) daughter of R. Szlomo. She died the 13th day in the month of Tevet year 5671 (1911) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a modest woman, the married [?] daughter of R. Icchok Zev(?). She died 14th day in the month of Shevat year 56??. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a modest woman, the married Hena Mirjam daughter of R. Joel Banem(?). She died 12th day in Nisan(?) year 5670 (1910) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a modest woman, the married Sheindel daughter of R. Aizik. She died 16th day in Nisan year 5667 (1907) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a modest woman, Gitil daughter of R. Jakob. She died 17th day in the month of Cheshvan year 5669 (1909) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a modest woman, the married Deborah daughter or R. Mordechai. She died the eve of [?] Elul year 5669 (1909) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

"Here lies a modest woman, the married Yonah(?) daughter of R. Peril(?). She died 24th(?) Tamuz year 5671 (1911) as the abbreviated era. May her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life."

A woman is most often described as 'modest' – once as 'proper', and a man as 'perfect' or 'perfect and upright' (Job 1:1). All deceased are married. Beyond these attributes the tombstones are silent as to the deceased's character, providing just the most basic formulaic details: name of deceased, name of father, date of death and closing abbreviation from I Sam 25:29: "May his/her soul be bound in the bond of everlasting life." These details are introduced by the all too familiar 'Peh Nun' "Here lies." No surnames are provided.

The choice of wood for a tombstone may be due to preference – as wood was a traditional Polish medium for construction, availability in resources, or simply to lack of affluence of the deceased or the community. The slender stylistic preference of the wooden tombstone, however, offered unique opportunities for the tombstone engraver/painter to accommodate the inscription in ways uncommon to stone inscriptions. To date, less than a dozen photographs exist of wooden tombstones in Poland before 1939. Yet this meagre collection still serves as a vital witness to a once distinctively common practice of marking the graves of Jews in Poland – a practice still apparentlly remembered in the ghettos during the Holocaust as evidenced by (at present) one remaining photograph from Radom, dated 1941 (Fig. 11). What is legible of this inscription reads: "Here lies the married Ruth (?) Henda [-----] daughter of R. Szlomo, may his light shine, Goldring. She died 16th Tevet 5701 (1941)."

Figure 11 Radom

Tomasz Wiœniewski, Bia³ystok (Poland)

Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D. , Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA (USA)

Polish text of Tomasz Wiœniewski translated by Mike Aylward, Maidstone (UK)

© Pictures, copyright 2008, from the Tomasz Wiœniewski collection www.bagnowka.com, include Druzhkopola Dru¿kopol – 1916, Kisielin – 1917, Lokache £okacze – 1915, Ozdziutycze – 1916, Pinsk Piñsk – 1918, Radom – 1941, and Wilkomir Wi³komierz – 1915.

This article is part of larger book album entitled, A History of Lost Jewish Shtetl Cemeteries, Publishing House KREATOR (http://www.iwk.pl), forthcoming 2008/2009

~~~~~~~

from the November 2008 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|