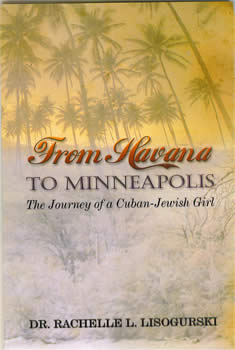

From Havana to Minneapolis: The Journey of a Cuban-American Girl

by Rachelle L. Lisogurski

Baltimore: PublishAmerica (2008)

ISBN: 1-60474-085-X

This is the tale of fond childhood memories that turned bitter with the Castro takeover of Cuba, then culminated with flight and adjustment to life in the United States. The author does not offer any new insights into the Cuban-Jewish experience. Instead, she provides an example of how political change dramatically affected the average person.

The author's father followed a typical pattern in Cuba. Although an Ashkenazi, he moved to the provinces (in this case Oriente), where he founded a business. Jews usually moved from peddling limited merchandise bought on credit to accumulating a substantial stock of goods to sell. Most Jews in the provinces were Sephardic, coming from Istanbul and Tarakya (European Turkey). With success in business Ashkenazim would move their wares into stores, while Sephardim would buy a vehicle and establish a weekly peddling route, moving from town to town.

Ashkenazim never really established communities in the provinces with the exception of Santiago de Cuba, where the European Jews tried several times to set up a synagogue and repeatedly failed. The Sephardim, however, were much more successful, setting up a national network of synagogues linked to Chevet Ahim in Havana. The Havana synagogue started in 1914, but real growth took place in the 1920s. Some of the Sephardic synagogues were buildings constructed for the purpose, while others were rented facilities, but even the most modest quarters provided a place for Jews to meet, pray, and socialize. So when success ensued, José Lisogurski moved to Havana and opened a fancier store. He had competition, but the 1950s was a decade of prosperity (at least for those who were already comfortable financially). Most stores did well, usually enjoying close association with American suppliers.

On 1 January 1959 life changed, as Batista fled, and Fidel Castro triumphantly declared the beginning of a new Cuba. Soon the new government initiated a new economic policy and a new life style in the officially atheist state. Lisogurski's store was nationalized. His hard-earned savings were limited to cash on hand. He felt that his life was crumbling and suffered a heart attack.

The author of this book was a young girl, when Castro's bearded forces marched into Havana in January 1959. For her Revolution soon meant the U.S. embargo on trade with Cuba and the introduction of ration books. Food was limited to staples, and even they were available only in limited supply. The new way of life also meant the nationalization of her school, the Centro Israelita, and the secularization of the curriculum. The Centro had been a landmark of Cuban Jewry since the 1920s. Now it and much of the once-thriving community were gone --- literally "gone," as Cubans started to flee the island. The kosher restaurant closed. The Yiddish newspaper stopped publishing after almost thirty years. Life had changed.

In many ways Raquel (today Rachelle) Lisogurski is a stereotype of Cuban Jewry. The family was not religiously observant but very Jewish in its outlook on life. They also remained in Cuba until 1968-1969 under the wishful illusion that in the end everything would be all right. Nor were they the only Cubans to remain, convinced that the Revolution would not last very long. One community leader loaned his car to the Embassy of Israel, exacting the promise that they would return it to him in a few months. Castro certainly could not remain in power that long!

In 1968 reality struck, and the opportunity to leave --- to leave home --- presented itself. The author boarded a plane for Madrid, then made her way to New York, not knowing if she would every see her parents again. She was a penniless teenage refugee in a new country, whose language she spoke only as a foreigner.

The second half of this book recounts adjustment to life in the United States, from the tropical climate of Havana to the cold winters in Minneapolis, from pounding the streets of Los Angeles to find a job as a key-punch operator to being a Ph.D. clinical psychologist in Minnesota.

Everyone has a personal story to tell. This is one of a lost childhood. Lisogurski enjoyed a joyful life that turned into frustration, escape from a tyrannical regime, and starting anew in a foreign land.

(For the record, Lisogorski's parents were fortunate enough to leave Cuba in 1969, but not without paying a price. As soon as they filed for exit permits, their subsistence payments abruptly ceased.)