|

Book review

by Jay Levinson

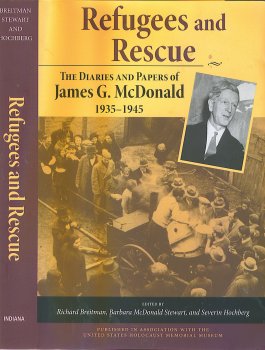

Refugees and Rescue: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1935-1945

ed. Richard Breitman et al

Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press (2009)

This is the fascinating diary of James McDonald, later to become the first United States emissary to the State of Israel. The volume provides keen and thoughtful insight into the political machinations of 1935-1945, when McDonald served the League of Nations and later American President Roosevelt in various positions regarding the plight of refugees.

McDonald had met Hitler in 1933 and came away with an impression of a masterful manipulator acting with ruthless preplanning, always calculating how his designs could be put into effect. He writes that those who dismissed the dictator as an incompetent character were making a serious error. Later McDonald wrote that the Nuremburg Laws were no spur-of-the-moment proclamation; they were carefully thought out by Hitler, who patiently awaited the opportunity to get away with their promulgation and subsequent enforcement.

There were those who thought that Hitler's régime could be tumbled by economic sanctions meant to weaken an already problematic economy. Oddly enough, at one point McDonald thought that the obverse was true --- some negotiation might be possible, as the Germans could be enticed by economic advantages in exchange for releasing Jews. He abandoned that view as Hitler became more entrenched in hate and became unswerving in his positions.

Göring was viewed with strong disdain. McDonald saw him as a hate-monger with whom no discussion was possible on any topic. McDonald provides a personal insight into the Nazi's nature. Göring boasted about his house, the most elegant residence in all of 1930s Berlin.

The future was clear to McDonald. As early as 1935 he foresaw the strong possibility of Hitler's instigating a general European war.

Insight led to frustration. The League of Nations was incapable of acting on the refugee issue, just as it failed on other subjects. One country even had the audacity to block movement, stating that the cancellation of basic rights for the Jews of Germany was an internal matter giving no other country the right to meddle. In retrospect this sounds nothing short of absolutely ludicrous. It yields the serious question of when foreign countries have not only the legal right but also the moral responsibility to intervene.

McDonald had close relations with key members of the Jewish communities of Germany, England and the United States. Again in 1935 he explicitly warned that the Jews of England and the U.S. had to be awakened to the gravity of the situation in Germany, where Jews had no future.

In historical retrospect the Munich Agreement is seen as the epitome of naïveté as Chamberlain trusted the Germans and declared that he had achieved "peace in our times." One quote in this book must be given serious thought. According to the quote, Munich was a signal particularly to the British of true German intentions. The agreement bought time for the British to prepare for all-out war, a step that they had previously been reluctant to take seriously despite obvious Nazi preparations.

A key question is why the United States did not open its gates to refugees. Even worse, Americans made entry more difficult as the situation in Germany deteriorated. Unfortunately, McDonald did not keep a diary for many of the critical years of decision, but the editors of this book do an excellent job of reconstructing the period from official documents and the letters and notes of others.

Where did President Franklin Roosevelt stand on the refugee issue? There is no simple answer.

A basic thought at the time was that the United States should not bear the brunt of a European problem. Herzl pushed for Jewish settlement in Uganda. The ideas of the 1930s and early 1940s favored former German colonies, Angola, Bolivia, the Dominican Republic --- and if the United States, then Alaska.

It is not to be debated --- FDR was a master politician with an excellent feeling for public opinion. He knew just how far he could go, both with the public and with the Congress. Against this background general acceptance of Jews during the 1930s and 1940s was not what it is today. There was resentment. There was open anti-Semitism. The polite euphemism about those earmarked for "special" treatment by the Nazis was "refugees," and there were non-Jews who fell into the category. No one, however, was fooled. The real intention of the term was Jews. There is no indication that FDR harbored any anti-Jewish feeling, but he certainly was aware of it in many sectors of the American populace.

Although Roosevelt did lamentably little to enable Jews to enter the United States, one indication of his positive attitude was his receiving McDonald several times in the White House. McDonald's views were well known to the president, and McDonald did not shun from making them known. Another voice the president could obviously not silence was that of his wife, Eleanor, whose contacts on admitting refugees he did not limit.

One tends to think of the President of the United States as an omnipotent personage who can direct government officials to do all that he wants. On many issues the opposite is true. FDR was sometimes an impotent leader á la Don Quixote who fought government bureaucracy in a losing battle.

The chief opponent to the entry of Jews was Breckinridge Long (1881-1958), head of the State Department Visa Section, who made every effort to place obstacles in the way of those wanting to enter the country. Was he an anti-Semite? Was he xenophobic? Was he a zealot American patriot afraid of German spies placed amongst political refugees? The truth probably lies with varying degrees of positive answers to each of these questions. There was one issue, however, to which there is a clear answer. Long wrote in his papers that McDonald hated him. Let there be no doubt --- he was right!

This book is not easy to read. It is a diary without the free flowing style of a novel or history book. The editors very capably annotated the volume, identifying people mentioned and filling in gaps with supplementary material. The subjects raised can keep the reader enticed. But, it is still a diary (that should absolutely be read by anyone looking for a better understanding of what happened).

~~~~~~~

from the June 2009 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|