Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

A REFUGEE LIFE: SHANGHAI 1939-1949

© 2009 By Audrey Friedman Marcus

and Rena Krasno (z"l)

Few people are aware that 20,000 European Jews, fleeing the Nazi scourge, found sanctuary in Shanghai, China in the late 1930s. Why was Shanghai such a popular choice? And why were there no restrictions on immigration as there were in other countries? Following is a short explanation, as well as an overview of the existing communities of Jews in Shanghai as the refugees began to arrive.

Shanghai became an Open Port after the China's defeat by the British in the Opium War and the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1843. Eventually, there were 80 such treaty ports, all totally open to foreign investment and colonization. In truth, there was no one to stop anyone from entering any of these open ports, and no visa, proof of capital, or landing fee was required.

Several years after the Treaty of Nanking, David Sassoon, a powerful businessman of Iraqi origin, and President of the Jewish Community in Bombay (India), sent his son to open an office in Shanghai. Other Sephardi Jews followed and contributed to the development of Shanghai into a booming world metropolis. They built modern buildings, developed trade, made philanthropic contributions, and became an important factor in Shanghai for almost a century until the Communist revolution.

Other Jews fled to China from Russia in the early nineteenth century, escaping from cruel pogroms and revolutions. In the beginning, these Jews had a very difficult time in Shanghai, since most spoke no English and it was difficult to compete with illiterate Chinese who were ready to work for starvation wages . However, in time, they opened small businesses, learned English, started working for British companies, and finally some became professionals: doctors, lawyers, and teachers, forming a new middle class.

Thus, when the European refugees, fleeing from Hitler, arrived in Shanghai, there were already in existence two different, well established Jewish communities.

As Nazi persecution of Jews increased in Europe, some 20,000 Jewish refugees poured into the open port of Shanghai. Most had escaped with only the clothes on their backs, a suitcase, and 10 Marks (U.S.$2.50), the paltry amount permitted each person. Their survival was the result of superhuman efforts by other Shanghai Jews and generous funding from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

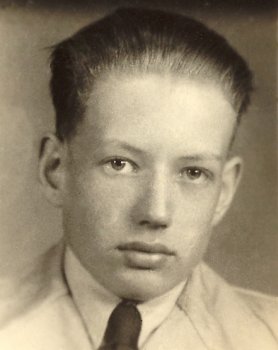

One of these refugees was 15-year-old Fritz Marcus, who arrived in 1939 with his father. The following account is based on his surviving diaries, which provide a remarkable and true picture of Shanghai during and after Japanese occupation and admirable courage and determination in the face of many difficulties.

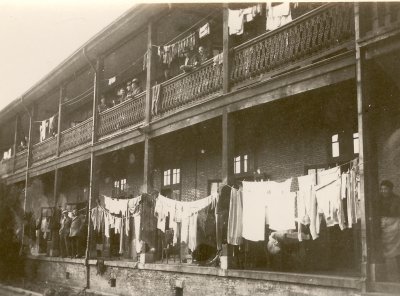

Ward Road Heim 1939

Fritz and his father and the newly arrived refugees were taken to a Heim (literally, a home, but more accurately, a camp) in an area of the International Settlement called Hongkew, which had been partially reduced to rubble during previous Sino-Japanese conflicts. Most were soon able to sell belongings in order to leave the Heim and rent a room elsewhere, but some remained in the Heime during their entire stay in Shanghai. All struggled to become acclimated to their new surroundings and to scratch out a living. Thanks to the "Joint," there were soup kitchens, a daily loaf of bread, and stipends for those who needed it. Ambitious refugees succeeded in opening small businesses and restaurants.

Early Life in Germany

When Fritz Marcus was a boy, he saw Hitler twice. The first time, as he was walking toward his favorite destination, the Zoo, near his Berlin home, he observed large crowds blocking the pavements as open limousines rolled slowly by. Hitler sat erect in one of them, his arm stiffened in the Nazi salute. Mobs of tearful, ecstatic women raised their children toward the Fuehrer, like disciples seeking the blessing of a saint.

The second time, the scene repeated itself in another part of Berlin. The throngs were so tight, so thick, that young Fritz could not squeeze through. Panic seized him as he was pitilessly shoved by the uncontrolled mob. Finally, when someone yelled that a child was in their midst, people stepped aside, leaving a narrow passage for him to get away.

The political situation in Germany was changing rapidly. Street fights between the adherents of National Socialism and the Communists became a daily occurrence. Teachers were greeted each morning with "Heil Hitler." Every day, Fritz's non-Jewish schoolmates sang lustily: "Und wenn das Judenblut vom Messer spritzt dann geht's nochmal so gut" (When the blood of the Jews spurts from the knife, then everything is going well again). Uncomfortable as one of the few Jewish students in his school, Fritz switched to a Jewish high school.

Fleeing the Homeland

On July 1938, Fritz's mother died after years of heart disease. Several months later, on the night of of November 9th and 10th, the Nazi rampage known as Kristallnacht convinced Fritz's widowed father that the time had come to leave Germany as quickly as possible. By then, however, most countries had closed their gates to refugees pouring out of Europe. Shanghai, China, was one of the very few remaining possibilities. Armed with German passports stamped with a large "J" for Jew, Fritz and his father Semmy set off from Genoa on the 7,000 mile sea voyage to Shanghai. After 29 days, they reached Shanghai on April 25, 1939.

The landing in Shanghai was a shock. The confused traffic of cars, rickshaws, wheelbarrows and carts, the cries of coolies, the piercing sound of policemen's whistles, the smells of garbage, human sweat, gasoline, and occasional whiffs of opium stunned the newcomers.

The refugees were taken to the Ward Road Heim. Conditions in the Heime were very primitive: numerous beds lined large rooms, families were separated by hanging sheets, food was barely sufficient for survival, and there was a total lack of privacy. Fritz and his father were able to sell a cut crystal fruit bowl, which enabled them to rent a small room.

Both Sephardi and Russian Jews did their utmost to help the nearly 20,000 newcomers survive. American Jews transferred funds. Still, the refugees faced many serious problems, including endemic illnesses such as small pox, cholera, typhoid, yellow fever and diphtheria; polluted fruit and vegetables due to the use of human "night soil" as fertilizers; shortages of food; a serious lack of medical supplies due to the war in Europe and the approaching Pacific War; crowded and unpleasant housing conditions; and difficulty earning a living.

Shanghai, already partially occupied by the Japanese, was on the brink of total occupation by the Imperial troops. British, French, and U.S. troops were departing. The city, now bursting due its burgeoning refugee population, was being abandoned.

After Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941 and December 8 in Shanghai), Japanese troops armed with bayonets arrogantly marched through the main streets of Shanghai or sped by in military vehicles, scattering frightened pedestrians. As the Pacific War progressed, the influx of European refugees came to a standstill. Then, on February 18, 1943, a frightening Proclamation was issued by the Commanders-in-Chief of the Japanese Army and Navy in Shanghai. All stateless refugees who had arrived in the city after 1937 were ordered to move into a two and a half square kilometer area in Hongkew. Although the word "Jew" was not mentioned, the Proclamation referred only to Central European Jewish refugees. Stateless Russian Jewish refugees who had arrived long before this date were not required to move.

Fritz described this unexpected turn of events:

"They [the Japanese] did not need to establish any fences or walls to keep us prisoners, because it was very simple to recognize that every Caucasian leaving the area was a refugee. (The Chinese in the area could come and go as they pleased.) All the Japanese had to do is to place signs at the intersections leading out of the Designated Area with the words: "Stateless Refugees Are Prohibited To Pass Here Without Permission." It was a rather fiendish scheme on the part of the Japanese that they did not put us in a camp. They simply restricted our freedom, our liberty, and our mobility without assuming responsibility for feeding or clothing us, or for providing us with medical care. We were on our own."

To obtain a permit to leave Hongkew, Jewish refugees now had to line up, sometimes for several consecutive days, before two Japanese named Ghoya and Okura. These officials arbitrarily accepted or rejected their requests for a daily or weekly pass. Ghoya, in particular, was known for humiliating and even physically abusing applicants. He proudly referred to himself as "The King of the Jews."

The existing Jewish community, the Sephardi Jews from Iraq and Russian Jews, joined together to organize various committees to come to the aid of the refugees, but encountered many obstacles. During the meeting of board members of the Shanghai Russian Ashenazi Jewish Community, all participants were arrested by the Japanese military police and sent to the notorious Bridge House Prison. Mr. Boris Topas, the President of the Board, was tortured for ten months, then literally thrown out on the street. Broken in body and spirit, he could never speak again.

Shanghai citizens now fearfully anticipated each day new Japanese restrictions and proclamations. Radio sets were strictly controlled and it became very dangerous to listen to short-wave news from abroad. The Japanese warned:

"…Those who possess the forbidden set shall speedily convert it according to regulations and obtain and authorized certificate….

…Those who have violated the provisions of this Proclamation or benefited the enemy of Japan shall have their receiving sets confiscated and be severely punished according to military regulations.

Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Expeditionary Forces in China

Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Seas Fleet"

Life became more and more difficult for Fritz and his father. Then, at the beginning of April 1944, Semmy Marcus fell ill and was taken to the hospital. At the same time, Fritz was ill with pneumonia and because he was running a high fever, he could not accompany Semmy to the hospital. On May 1, 1944, Semmy Marcus died. When told of this tragic development, Fritz wrote in his diary:

"…The room seems to turn around me. I have to close my eyes in order to grasp fully the meaning of the news. A feeling of complete helplessness overcomes me. I don't know what will become of me...I feel only one thing: loneliness. My Vati, with whom I had shared every thought, from whom I had no secrets, who was the backbone of my life, I would never see him again…"

Semmy Marcus's funeral took place on May 3, 1944. Sadly, his distraught young son could not leave his sick bed to attend.

Alone in a Strange Land

It was not easy for Fritz to make his way alone after Semmy's death. He often referred to this period as the nadir of his life: he was without a country, had no parents, had not finished high school, and had no apparent way to make a living. Gradually, due mainly to the loving attention given him by Hugo and Kaethe Alexander and their son Theo Rolf, who became his lifelong best friend, Fritz was able to pick up the pieces of his life and carry on.

In order to pay the funeral expenses and earn enough money to survive, Fritz reluctantly sold some of his Bar Mitzvah presents. He attempted to carry on a small business begun by his father, importing buttons from Japan and selling them to several Shanghai shirt makers. Additionally, he ran frequent errands for other refugees, renewing their radio licenses and using his pass out of the Designated Area to make purchases for them in other sections of the city. He gladly performed any odd job that was offered him. He also tried selling wurst, nougat, and dress designs, but was never very successful as a salesman.

The one meal a day provided by the Jewish community, though scanty and not always tasty, was a godsend for Fritz. Often ill, he was able to obtain medical treatment from the community.

Cultural and Religious Life

Many of the young people in Shanghai went to schools underwritten by Horace Kadoorie, a wealthy Sephardic businessman. Fritz, too old for these schools, continued his education by frequently attending lectures. At each meeting of the cultural club started by his friend Theo Rolf, a member gave a lecture, which was followed by a lively discussion. Fritz chose to speak about Disraeli, the influential British Prime Minister under Queen Victoria who had converted from Judaism to Christianity. Fritz seldom missed the lectures given by Professor Willy Tonn, a Sinologist, who offered classes on Chinese history and customs. There was a rich cultural life in the Designated Area, and he and his friends also went to many plays, operas, operettas organized by refugee groups, as well as to movies. Sometimes they put on their own dramatic or humorous productions.

Religious life in Shanghai was rich and varied. There were Orthodox worship services, as well as more liberal services. Fritz celebrated Jewish holidays with the Alexander clan and attended liberal services, which were held in their home at first, later moving to a movie theater. The joyous nature of their observances remained a lifelong influence. A member of the High Holy Day choir, Fritz also learned to chant the portion from the Book of Jonah and did so each subsequent year.

Wartime Deprivation and Final Victory

After Pearl Harbor, the situation for the refugees became even more difficult. Funds from the United States were cut off due to the Anglo-American Trading with the Enemy Act. There were critical food shortages. Tempers were short and suicides increased. Yet, through it all, Fritz faced his life with courage, fortitude, and determination, never complaining. Despite often serious financial difficulties, he always tried to make the best of his precarious situation.

Fritz and the other refugees avidly followed the progress of the war in Europe, particularly the situation on the Russian Front. Many, including Fritz, mounted maps on the wall, marking the victories and advances with pins. They were able to receive news of these battles by listening to the Russian radio station. However, due to Japanese censorship, they remained ignorant of the true facts about the war in the Pacific; the only news they heard consisted of Japanese propaganda, which made it appear that the Japanese were winning at every turn. Rumors circulated constantly, but few accurate facts were available.

When the war in Europe came to an end, there was great rejoicing. However, the surrender created little change in the critical situation for refugees in Shanghai. All their hopes and dreams were focused on the eventual end to the Pacific War.

On August 9, 1945, Fritz read the following Japanese report on the atom bombing of Hiroshima in an English language Shanghai newspaper:

"ATTACHED TO PARACHUTES

A small number of B-29s penetrated into Hiroshima shortly after 8 a.m. on August 8 and dropped a number of explosive bombs, as a result of which a considerable number of houses in the city were destroyed and fire broke out at various places. It seems the enemy dropped new-type bombs attached to parachutes which exploded in the air. Although details are under investigation, their explosive power cannot be made light of.

News of the Allied victory spread like wildfire in Shanghai, but it was only on August 11 that Fritz became completely convinced that the war was finally over. The evening papers stated that Japan had accepted the Eight Points of the Potsdam Ultimatum. On August 15, the Japanese emperor publicly declared that Japan had surrendered".

In the former Designated Area, large banners with the blue and white Star of David now flew over the Heime. Lights burned all night, while American marches were played on the radio. Everywhere paper flags of the U.S.A., Great Britain, China, and Russia were sold. On September 1, refugees danced together at a wildly happy party in the building where Fritz lived.

Postwar Adjustments

Fritz continued working at his various jobs and looking for a real job now that the Japanese were no longer in control. His big break came when Theo Rolf Alexander (now calling himself Ted) recommended him to the manager of the Cathay Hotel and he was hired as a receptionist. The Art Deco Cathay Hotel (now the Peace Hotel), the tallest building in Shanghai, was famous throughout the Far East for its luxurious rooms, elegant ballroom, and outstanding dining facilities. It had been built by Sir Victor Sassoon, a scion of the very wealthy Sephardic Jewish Sassoon family. As a result of his job at the Cathay Hotel, Fritz had the opportunity to meet many prominent World War II personalities, including General Albert C. Wedemeyer, who during the war was Commanding General of the U.S. Forces, China Theater; Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault, founder of the American Volunteer Group that became known as the Flying Tigers; and former President Herbert Hoover, who was sent by President Truman on a mission to study the food situation in various countries.

Shanghai now changed rapidly. Instead of bayonet armed Japanese troops, tall, impeccably dressed, smiling American GIs were enthusiastically welcomed by crowds on the streets. Fritz admired the happy-go-lucky, gum chewing Americans and emulated their ways. He smoked American cigarettes, drank American beer, ate American food, and went to American movies. People now called him "Fred."

Not until the autumn of 1945 did the refugees learn in detail the full depth of the catastrophe that had decimated European Jewry. Synagogues in Shanghai held prayer meetings to memorialize those that had perished. Although Fred did not lose any relatives in Germany, many of his friends learned that their families had been killed in mass murders. The horrifying tidings caused great grief, but at the same time the European refugees were deeply grateful, realizing how fortunate they were to have found sanctuary in Shanghai.

Due to the intensifying civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists, tensions rose in Shanghai and local unrest increased. Local Chinese organized strikes and demonstrations. Many were deeply disappointed by U.S. support of the corrupt Chiang Kai-shek regime. The future of Jewish refugees was uncertain, and they feared for their future. In order to emigrate, one needed a collective affidavit provided by one of many aid organizations or an individual affidavit from a reliable resident of the country where the refugees hoped to start a new life. These affidavits provided guarantees that the new immigrants would not become a burden on the state.

Fred as Receptionist at the Cathay Hotel 1947

Fred was not exempt from these concerns. He desperately hoped to emigrate to the United States, as did most of his fellow refugees. To be on the safe side, he also applied for a visa to Brazil and considered Australia as a second backup. As his worries increased, he began to drink frequently and to meet Chinese "dancing girls." Would he be trapped again if the Communists controlled Shanghai? How could he get a visa to another country? Where could he go? His health continued to deteriorate. As a diversion from his deep concern about his uncertain future, he organized excursions to the surrounding countryside for his friends. He also enjoyed his first vacations and took several trips into the interior of China.

One by one, Fred's friends began to leave, most for the U.S. About 20% of Shanghai's Jewish refugees chose to go to the newly established State of Israel. Others left for Canada, South America, and Australia. Farewell parties took place almost daily, and those who remained behind engaged in agitated conversations centered on emigration, affidavits, and visas. The situation in Shanghai continued to worsen as the value of the Chinese currency plunged almost hourly. Yearning for love and comfort, Fred became smitten with a young woman named Thea. Together they enjoyed many cultural events, parties, and bicycle trips into the nearby countryside. In spite of these pleasant experiences, inner peace evaded him.

In October 1948, Fred finally obtained a collective affidavit from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and was granted a visa for the U.S. Prior to his own departure, he volunteered with U.N.R.R.A. (United Nations Refugee Rehabilitation Association), helping with boarding procedures on ships transporting refugees to the U.S. As always, he performed his duties with in a capable and responsible manner. A period of frantic activity followed: formalities required by the U.S. Consulate, winding down his job at the Cathay Hotel, attending farewell parties, making arrangements to transfer his savings to a San Francisco bank, disposing of some possessions, and packing.

On February 3, 1949, Fred boarded the S.S. Joplin Victory bearing excellent testimonials from his places of employment, and with fervent hopes of building a stable future. As the ship sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge. a fellow passenger standing next to him on the deck put his hand on his arm and said, "Fred, we're home."

Postscript

Shanghai and the necessity for hard work and a courageous approach to life's difficulties stood the refugees in good stead in their new countries. Like most others, Fred thrived in the U.S. Not long after his arrival in San Francisco, he obtained a job as a receptionist at the Huntington Hotel on Nob Hill. After a time, he was promoted to Assistant Manager. He became a citizen of the U.S., married his first wife, and had two children. To earn additional funds to support his family, he did part-time work as a director of education in various Jewish Sunday Schools in the Bay Area. In the early 1960s, Temple EmanuEl in San Jose invited Fred to become their full-time educator. During the 17 years he was employed there, he earned an undergraduate college degree and a masters degree in Jewish education. He became successful and well respected in his new field. In1980, he was elected President of the National Association of Temple Educators.

Fred's first marriage ended in divorce, and in 1974 he married Audrey Friedman Marcus, also a Jewish educator, and the founder and executive vice president of a publishing company that produced materials for teachers and students in Jewish schools. Their five children and nine grandchildren revered and admired Fred as the loving patriarch of the family. He devoted his free time to giving frequent talks to school children, teachers, and church and synagogue groups about growing up in Nazi Germany and the refugee experience in Shanghai. He favored reconciliation between Jews and Germans, stressing that we must forgive, but never forget, the lessons of the Holocaust.

After retiring from Jewish education, Fred embarked on a third career as a travel consultant in Denver, Colorado. He and Audrey traveled the world, together visiting 108 countries. They went twice to China where Fred was able to show Audrey the places he remembered from his refugee days. Most likely due to his difficult experiences in Shanghai, he suffered from heart trouble and underwent bypass surgery in 1983. In 2002, on one of his many trips back to Germany, Fred suffered a third heart attack. He died in a German hospital, an irony not lost on the rabbi who delivered the eulogy at his funeral.

#####

Audrey Friedman Marcus and Rena Krasno (who passed away in October 2009) are the authors of Survival in Shanghai: The Journals of Fred Marcus 1939-49 (Pacific View Press), available at www.fredmarcusmemorialwebsite.com, as well as from online booksellers.

~~~~~~~

from the January 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|