Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Jews Fighting Hitler

By Jay Levinson

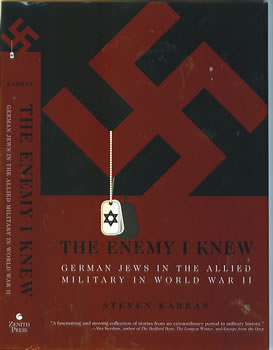

The Enemy I Knew: German Jews in the Allied Military during World War II

by Steven Karras

Minneapolis: Zenith Press (2009)

ISBN 978-0-7603-3586-4

This is not a dry academic analysis of the motives of German Jews to fight in Allied armies against the Nazis. Rather, this is a collection of twenty-seven personal interviews in which people recollected their emotions more than fifty years after World War II. Some of those relating events are known, such as Henry Kissenger. Most, however, are faceless Jews who stepped forward to serve their newly found country in time of need.

If there is a common thread that runs through these accounts, it is the post-World War I feeling of being German, the betrayal of society during the Hitler regime, Americanization, and the intense motivation to rid the world of the Nazi threat. Many of the refugees-turned-soldiers were appalled to see former “friends” turned into rabid anti-Semites. As one person phrased it, this was a generation drunk on the propaganda of hate.

After Hitler’s rise to power one girl came home, swastika on her blouse, enthusiastically shouting, “Heil Hitler,” until her father called her aside and told her that although she had been baptized and brought up as a Lutheran, she was in fact Jewish. Flabbergasted, she eventually returned to her Jewish roots, emigrated to Palestine, and was assigned by the British Army as an ambulance driver in the right again Rommel.

Most of the soldiers interviewed in this book (in fact initially for a movie also made by Steven Karras) were drafted for the U.S. Army. Many were new and naïve Americans, who did not understand the rigidity of military life. One worked on an electronics device that he felt would certainly help the army; he was turned away, essentially because the innovation was not in his job description. There were those who learnt quickly. As one person summed up, in basic training do not think, and play by the rules; in war, think, and forget the rules.

Sometimes satisfaction takes odd turns. While Jews were still permitted in German schools, one pupil was forced in front of his class as his teacher demonstrated, “This is how you beat up a Jew.” Years later that former schoolboy returned with the U.S. Army and had the pleasure of ordering that teacher to pull weeds in the Jewish cemetery. He was one of several German Jewish soldiers brought to their childhood homes to identify earlier Nazi supporters.

The Jews in these stories all knew German, and many functioned as translators Their was obvious pride in translating the words of prominent officials of the deposed regime such as Hermann Göring (arrogant to the end) and Julius Streicher (a meek man when stripped of his official regalia). In other cases the Americanized Jewish soldiers interrogated Germans wearing Nazi uniforms, whom they had known not so many years previous.

The tales of battle are mind-boggling, as young men risked life and limb for an ideal. Words can never express the fear and trepidation, the courage and bravery, of those who fought. How does one describe the death of a close friend who was a co-combatant just seconds ago?

There are also reminiscences of forgotten incidents. One Jewish soldier relates the incident of a burglar released from a British prison and assigned to Allied forces in Normandy. He boasted there was no building he could not break into, and he has told to use his skills as part of the Allied advance.

In reading these accounts it is hard not to take notice of Jewish holidays, particularly during the Autumn 1944. Some soldiers managed a symbolic or short observance, but the Front was fluid, and often troops were on the move. There was no time to stop. There was no possibility to stop.

Perhaps the most moving story is that of Manfred Gans, formerly of Borken, Germany. He enlisted in the U.S. Army and was part of the assault on Normandy’s “Gold Beach” at H-Hour on 6 June 1944. On 7 May 1945, before Nazi unconditional surrender was known to all German troops, Gans received permission and set out on a 150 mile trip to Theresianstadt. He came to the camp entrance, and the guard allowed him entry against orders. The area was under quarantine because of rampant disease. Gans made his way to the camp registrar, a Dutch woman, and the two searched records for two internees. The Dutch woman found the two, “I have a very joyous message for you.” One of the two looked up, “Are we getting some extra food?” The Dutch clerk then responded, “No. Your son is here.”

Editing of the book is poor, but one wonders how good it should be to retain the authenticity of verbal interviews. There is also too much detail on military units and troop movements for the average reader, but the narratives are fascinating.

~~~~~~~

from the June 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|