|

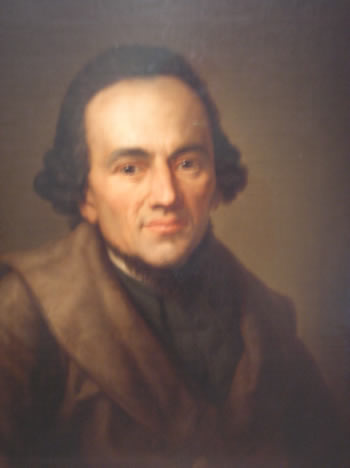

Moses Mendelssohn

By Larry Fine

One of the most influential people in modern Jewish life, whose influence in still felt today, was Moses Mendelssohn. Born in 1729 to a poor Jewish family in Dessau, a town in Germany on the junction of the rivers Mulde and Elbe, his father, Mendel, was a poor scribe and Moses later took the family name based on his, Mendelssohn, meaning Mendel's son.

Like most young Jewish children at that time, he received a traditional Jewish orthodox education and as a boy, he quickly advanced in his studies. His teacher was David Frankel who was for a time the rabbi of Dessau. When he became chief rabbi of Berlin in 1742, a very young Moses followed him there to continue his education. Rabbi Frankel helped his student gain entrance to Berlin since Jews were not wanted in the German cities and needed permission from the local city council to reside in German towns. Rabbi Frankel helped him to be accepted in the city and to find a place to live. The learning in Rabbi Frankel’s yeshiva was exacting and tedious, but young Moses was an astute student and learned well. He managed to make a small bit of money by copying texts that his teacher needed for print. With this money he bought bread, often this was his only food, which he often made last for the entire week.

At that time there was a cultural separation between the Jews and Germans that made any social contact extremely difficult. Jews, with a few notable exceptions, were rarely allowed out of their ghetto, and certainly it was rare that a Jew could learn in one of the German universities. The Jews were subject to many laws that separated them from the Germans who discriminated against them in the most harsh terms and taxed them at exorbitant rates. They were not allowed to come and go as they pleased but were required to live in the crowded ghetto were available space was very limited and thereby raising prices for living quarters very high, much higher than what was available outside of the ghetto. Secular education was frowned upon by the Jews and even knowing or speaking the German language was rare; the Jews spoke a dialect called “Judendeutch” which is today called Yiddish. If yeshiva man was caught reading a secular book or a book in German, he would be expelled from the yeshiva, which would mean expulsion also from the German city in which the yeshiva was located.

Mendelssohn taught himself German, Latin, Greek, French and English alongside of his talmudical studies. He was careful to do this in secret for the mere possession of books of this sort was enough to be asked to leave or even excommunicated in extreme cases. In spite of this, Mendelssohn became fluent in German in a very short time.

His talents and capabilities were noticed by other young wealthy Jews who due to their father’s wealth were able to study secular studies. One of these was Moses Solomon Gumpertz who had the distinction to be the first Jew to graduate from a German university as a medical doctor. Another young man in the group introduced Mendelssohn to mathematics and another introduced him to philosophy. Although he had read Maimonides' Guide to the Perplexed, a book with philosophic meaning, he now read John Locke's Essay concerning Human Understanding in Latin. This book began his intellectual adventure. Mendelssohn was self taught; there were no universities in Berlin then, and even what was available was denied to him, being a Jew.

In 1750, Mendelssohn decided to end his studies with Frankel. He decided not to receive ordination as a rabbi but rather to become a tutor for the sons of a wealthy Jewish Berlin silk merchant named Isaac Bernhard. In this manner he was able to extend his residence permit as an indentured member of the merchant's household. The merchant liked Mendelssohn and with his tutoring Bernhard‘s children, he earned enough money to purchase books. His reading included Spinoza, Aristotle, Plato, Newton, Rousseau, and Voltaire, just to mention a few. For the next four to five years he taught himself as well as his master's children.

While in Berhard's house he experienced an atmosphere of limited enlightenment, as accustomed to a wealthy Jewish business man. While there, he met many Jewish and non Jewish intellectuals. Two young men that he became friends with were Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a budding playwright and journalist and Friedrich Nicolai, a bookseller and liberal publisher. They formed a circle or society which later became known as the Berlin literary school. Together, they discussed philosophy, religion and politics. They were committed to bringing about an enlightenment which was described as the liberation of man from own immaturity by giving him the ability to think for himself. Enlightenment mean different things to different people. In England enlightenment was mostly concerned with the economy, in France it was concerned with liberalizing the political system, in Germany enlightenment focused on ensuring freedom of faith and belief.

Lessing, the son of a Lutheran pastor, preached tolerance and the rule of reason. He utilized his skills in writing to promote religious tolerance. His play, “The Jews” which was written before he met Mendelssohn, raised a storm by suggesting that Jews had virtues like other humans. Germans were raised with the concept that Jews were of a much lower character than the Christian; the fact that the Christians deprived them of every means to make a livelihood, to receive a secular education, to receive equal protection from the law and to live as a free man, and instead attended churches which preached hatred towards them, did not occur to them that this caused the Jews low position in Germany. To Lessing, Mendelssohn was living proof of one of the main tenets of the Enlightenment that a person can become something by force of his own thinking.

Friedrich Nicolai was the son of a bookseller and became Lessing's and Mendelssohn's devoted publisher. The three would met each day and discuss literature and philosophy. The experience of these two devoted friends, plus the other intellectuals that he came in contact with in their company convinced Mendelssohn that Jews and Germans were on the threshold of a new liberal age in which they would live together in peace and harmony.

Although he had contact with many non-Jews and many liberal ideas and philosophy, Mendelssohn maintained his personal strict observance of Jewish law and never deviated from it. He strictness in religious observance never taxed their friendship. Later in life, when Mendelssohn was married, the two friends would come over to visit Mendelssohn on Friday night. Mendelssohn would excuse himself declaring his intention to go into the next room to receive the Sabbath Queen. He would remind them that tomorrow on the Sabbath, he would not be able to go to join them, but they were welcome to come to visit him, which they did.

In 1755, Lessing brought a book by the English philosopher Anthony Ashley Cooper to Mendelssohn to read. After he read it, he was asked what he thought of it. Mendelssohn replied that it was quite good, but who needs a book like that if he could write the same thing. Lessing challenged him to do so. In a short time Mendelssohn handed Lessing a manuscript called Philosophical Dialogues as proof that he could quite easily duplicate Cooper‘s work. Several months later, Lessing surprised Mendelssohn with a printed and bound copy which had been printed by Nicolai's press. It was this book that launched Mendelssohn as a German author. Soon other books were to follow. The book, Phaidon, or the Immortality of the Soul in Three Dialogues was an immediate best seller and it was translated into several European languages. Its basic message was that reason was divine and gives man hope of the divine. Mendelssohn soon became one of the best know German writers. His books had an elegant style which was uncommon in German philosophic texts.

Mendelssohn became famous. Not since Spinoza had a Jew crossed the line to become a prominent personality in the majority Christian culture. His fame spread far and even Catholic monks wrote to him seeking guidance. The Prussian Academy of Sciences elected Mendelssohn a member. However since King Frederick II was the over ruling authority at that time and had the power of veto. He quickly vetoed the proposal prompting the remark that the only thing that Mendelssohn lacked was a foreskin! Mendelssohn took the rejection lightly remarking that it was better to be honored by the academy and rejected by the king than to be honored by the king and rejected by the academy.

In the meantime, Bernhard's son grew up and his services was no longer needed as a tutor so Mendelssohn became Bernhard's bookkeeper. There was an increase of salary but also an increase in the amount of time that Mendelssohn had to devote to his work. He longed for the time when he would have more leisure to pursue his own interests. Nonetheless, he became an attraction for many visiting intellectuals to meet “the Jew, Moses” there in this counting room surrounded with work; yet they found him good natured and able to engage in brilliant philosophic conversations as he processed the accounting of the business.

At this time he married Fromet Guggenheim and committed to himself to marriage. She was twenty-four and a head taller than Mendelssohn who was thirty at the time. Unlike most Jewish marriages at the time, it was not arranged through the agency of a shadchan, but rather they secretly became engaged on their own. He was introduced to her father only several months later.

Although he was still only an indentured household member, he was able to arrange a Prussian residence permit for her quickly. Upon the occasion of their marriage, he was required to pay the exorbitant tax extracted from Jews upon their marriage.

Soon after the marriage Mendelssohn was arrested and accused of defaming Christianity in his writings. Nicolai's literary magazine was shut down. It took several days but Mendelssohn was eventually cleared, but it brought home the message that his status of an indentured household member was precarious. He was urged to petition the king for a change of status. King Fredrick ignored him. Mendelssohn submitted another petition. The king agreed to grant Mendelssohn protected status, but not his wife and children which meant they could be expelled upon his death. In addition, the king demanded payment of one thousand thalers, now considering that Mendelssohn's monthly salary was twenty-five thalers the request was impossible for him. Still he submitted another request, requesting that the fee be waived. Mendelssohn's friends intervened on his behalf and were able to get the fee waived claiming that Mendelssohn was really an exceptional Jew, prompting others to say he was a very un-Jewish Jew.

Missionaries looked to Mendelssohn as a possible candidate for conversion. They reasoned that if Mendelssohn would convert, then many more Jews would follow him. To Mendelssohm, Christianity was no answer and undesirable as a religious belief. He admonished the missionaries that he would never abandon Judaism for Christianity since its 'revealed' dogmas contradicted reason. He declared that he is a Jew and shall remain one.

Although his bout with the missionaries left him intact as a Jew, he felt that it was time to engage in a Jewish reform. Although as a reformer, he remained personally committed to strict traditional observance even though he felt that change was necessary to prevent Judaism from become fossilized and losing its creativeness. He advised his followers to adapt the habits and constitution of the land in which you live but to retain the religion of your forefather. He also called for limits to the power of the rabbinate. He argued that true faith knows no force but that of logical persuasion and that rational argument is the path to bliss.

He wanted to revive to the study of classical Hebrew and to use German as the common language instead of the “Judendeutch” which was spoke by the Jews. Most Jews were at that time illiterate in the German language, the common language of the land. For this reason he began a translation of the Torah into German with the Hebrew words printed with German next to it to facilitate a quicker understanding. He felt that this would be the first step towards entering the German culture. Prominent rabbis were infuriated on his printing German on the same page as Hebrew and considered putting him in excommunication, but the attempt failed. His new translation proved very popular amongst the Jews.

It soon became fashionable in German society to begin to view Jews as people that have virtues and in limited cases, young Jews become acceptable in certain small pockets of German culture. Mendelssohn's own children, he had three sons and three daughters, lived in both cultures, the Jewish culture and the German one. Mendelssohn seems to have been aware that his eldest son had given up his Hebrew studies and was no longer strictly adherent to the tenets of Judaism. Two of his daughters, Dorothea and Henrietta, converted to Catholicism and later a son, Abraham, influenced his children to become Christians. Felix Mendelssohn was a grandson who converted to Christianity was a famous German composer.

Although Mendelssohn is credited with being the father of the Reform Movement since he was the advocator of reform but his personal views were not those of today's Reform Movement. He lived as an observant Jew and died the same. Yet his children did not follow in his footsteps.

Although Mendelssohn was a great philosopher and thinker. He believed in logical reason above all and that through man's use of his rational abilities it would bring mankind closer together. Unfortunately, mankind does not seem to have been on the same level as Mendelssohn.

A popular phrase is that hindsight is twenty-twenty, meaning that after the passage of time we can see clearer. There is no doubt that Mendelssohn was a great thinker, yet his greatness did not extend far enough to save his descendants from Christianity. They, using their logic, reasoned that there was nothing in Christianity except that conversion was a passport to affluence and success. Human logic has its limits and its flaws, our tradition may seem illogical, but it is all a Jew has to guarantee that his children have a continued Jewish existence.

~~~~~~~

from the June 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|