Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

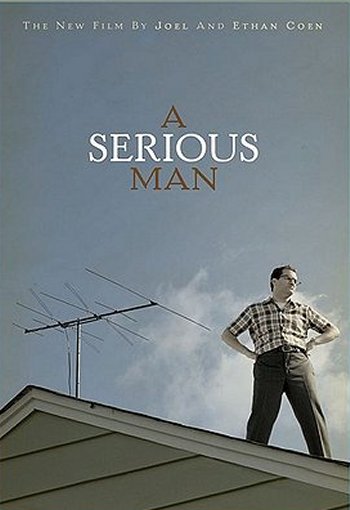

From Bontsha Schweig to Larry Gopnik: Re-Examining “A Serious Man”

By Ronald Pies

The movie, “A Serious Man”, written and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, raises a multitude of spiritual, philosophical, and metaphysical questions. The universe of the film’s main character, Prof. Larry Gopnik (played by Michael Stuhlbarg)—and perhaps the universe of the Coen brothers—is clearly not that of Einstein, who famously insisted, “God does not play dice with the Universe!” Rather, it is the universe of quantum mechanical paradoxes and Heisenbergian uncertainty. Furthermore , the Coen brothers seem to say, if there is an entity corresponding to God, there is little we can know or fathom about His/Her/Its ways.

That conclusion, of course, is nothing new: Maimonides (Moshe ben Maimon, ca. 1138-1204) said much the same thing eight centuries ago: the most we can ever say about God is what He is not; e.g., not finite, not corporeal, not imperfect, etc. Indeed, man’s abject incapacity to understand, much less our right to question, the ways of God was the central theme of the biblical book of Job. And, at the end of “A Serious Man”, when the tornado appears in the distance, we are reminded of God’s appearance “out of the whirlwind”, when the Lord puts a series of barbed questions to the querulous and self-justifying Job: “Will you even put me in the wrong? Will you condemn me that you may be justified?...(Job 40.6-9).

That the tornado in “A Serious Man” appears shortly after Prof. Gopnik sins (by accepting the student’s bribe) hardly seems incidental to the Coen brothers’ intentions. But—could this Minnesota “whirlwind” have been coincidental? Was Hashem punishing Prof. Gopnik, and perhaps the entire Jewish community, thus asserting the rule of moral order in the universe? Was the tornado—and the ominous call from Gopnik’s doctor—a manifestation of divine retribution? Or were both events merely random occurrences in a universe given over to mere chance? It is hard to read the Coen brothers’ intentions on these matters—which may be precisely their intention! But I believe that, aside from these metaphysical questions, the Coen brothers are playing with a very specific literary subtext in “A Serious Man.”

Many years ago, in a course on Jewish literature taught by Prof. Sander Gilman, I read the classic tale, “Bontsha Schweig” (“Bontsha the Silent”), by Isaac Loeb Peretz (1851-1915). Sometime after seeing “A Serious Man”, it occurred to me that the Coen brothers—serious students of Judaic lore—could not possibly have made this movie without Peretz’s story lurking somewhere in their conjoined fraternal psyches. It was only while writing this piece that I discovered a similar realization on the part of blogger Rabbi Joshua Hammerman [see http://joshuahammerman.blogspot.com/2009/10/seriously-funny-or-flawed-movie-or-god.html]--and, I strongly suspect that the two of us are far from the only ones who reached this conclusion.

If Rabbi Hammerman and I are correct, we first need to recap a bit of Peretz’s story before we can understand how it infiltrates and shapes the Coen brothers’ movie. Bontsha the Silent is a poor porter, “a human beast of burden”—but more than that, he is a kind of cipher. Peretz’s story begins by announcing Bontsha’s death, which “made no impression at all” on earth. Bontsha was “a human being” who “lived unknown, in silence, and in silence he died.” Bontsha existed like “a grain of sand” until one day when “…the wind at last lifted him up and carried him across to the other shore…”. (There’s that emblematic wind, once again). But in Heaven, the story is quite different. Bontsha is greeted by the Heavenly Host like a beloved son, come home at last. “In Paradise, the death of Bontsa was an overwhelming event.” But while Bontsha is greeted warmly, he is also presented before a kind of tribunal, where a prosecuting angel duels with a defending angel, presided over by an unnamed “judge” (some aspect of the Godhead, presumably). It is the defending angel, however, who dominates the trial—the prosecutor makes only a few token attempts at objection. The defending angel recounts the numerous times Bontsha had suffered abuse of one sort or another, yet said nothing in protest or complaint. The judge addresses Bontsha directly, and says,

“There, in that other world, no one understood you. You never understood yourself. You never understood that you need not have been silent, that you could have cried out and that your outcries would have brought down the world itself and ended it. You never understood your sleeping strength. There in that other world, that world of lies, your silence was never rewarded, but here in Paradise, you will be rewarded…Whatever you want! Everything is yours!” (Note, by the way, the reference to “that world of lies”—is this theme picked up in the words we hear in the Jefferson Airplane’s song: “when the truth is found to be lies….”?)

And for what does Bontsha ask? What supernal pleasure or reward does he request, after all his earthly suffering? Bontsha smiles and says, “Well, then, what I would like, Your Excellency, is to have, every morning for breakfast, a hot roll with fresh butter.”

The reaction among the Heavenly Host is utter silence—a silence

“…more terrible than Bontsha’s has ever been, and slowly, the judge and the angels bend their heads in shame at this unending meekness they have created on earth. Then the silence is shattered. The prosecutor laughs aloud, a bitter laugh.”

With Bontsha the Silent, Peretz seems to present us with what some might call, “a good Jew”—a decent, harmless, and uncomplaining man. But this is not what Judaic ethics would hold at all. From the rabbinical perspective, Bontsha is a kind of benign miscreant. Bontsha’s vermiform passivity and silence are not merely his undoing as a man, but—I would argue—also as a Jew. For Jews are meant to argue—and to protest injustice! The Talmud tells us, “Justice, justice shall you pursue” (Deuteronomy 16:20). The archetypal figure in this regard is Moses, who—upon seeing an Egyptian overseer brutally whipping an Israelite—hits the overseer so hard that the man dies. Furthermore, Judaic ethics affirms a robust right to self-defense and the need to preserve one’s self-respect. As Rabbi Hillel asks, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” (Pirke Avot 1:14).

Now: where does all this take us when we consider poor Professor Gopnik? Rabbi Hammerman writes that

“When Larry moved out of the house at the request of his wife and her lover, that's where he stopped being Job and morphed into Bontsha the Silent…whose passivity crosses that fine line from goodness to madness. Passivity is not good - nor is the biblical Job passive. Turning the other cheek is not a Jewish idea, especially with a guy who is making off - and out - with your wife. So Larry stopped being a serious Joban character at that moment for me, and this ceased being a serious attempt to grapple with Job.”

Indeed, I believe Rabbi Hammerman is right: Larry Gopnik is not Job—but neither is he entirely Bontsha. For unlike Peretz’s Bontsha the Silent, Prof. Gopnik is not “good to the last drop.” He falters. He sins. He takes a bribe. In essence, Gopnik is worse than Bontsha—he is a kind of “failed Bontsha”. The only alternative view requires us to suppose that when Larry Gopnik takes the bribe, he is somehow acting boldly and assertively—even if immorally. (I do not believe that Gopnik’s legal expenses can justify his taking the bribe, even if they help explain and perhaps mitigate his corrupt act). But if taking a bribe is construed as boldness, we are a long way from the world of Moses and Hillel!

So perhaps the Coen brothers are telling us that--even when held to the humble standards of Bontsha the Silent--Larry Gopnik is a pitiable failure. As the movie draws to a close, Larry has neither Bontsha’s scruples nor Moses’s courage. Larry leaves us “not with a bang, but a whimper.” And perhaps we are meant to believe that he is punished for this—that his dire medical news and the approaching tornado are meant as just retribution, and not merely the random play of chance in a lawless universe.

And yet, and yet: there is, after all, something redeeming in Larry Gopnik, at least as I experienced his character. Perhaps the one moment of redemption in the entire film is when Gopnik’s son, Danny, emerges briefly from his drug-induced, bar mitzvah stupor and begins to read his assigned portion from the Torah. Larry’s face lights up! It is more than mere relief: Larry has a moment of pride—in Yiddish, he “qvells”-- and we can imagine that he actually experiences a fleeting feeling of naches (joy). A mere worm could not experience such exaltation, even if the moment has the half-life of one of Prof. Gopnik’s subatomic particles. These feelings are the hallmark of a man-- in fact, of a mensch. For all his failings—and they are legion—we may say of Larry Gopnik what Hamlet says of his late father: "He was a man, take him for all in all.”

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Frederick Miller MD, PhD and Alan Stone MD for prompting many of the ideas contained in this essay. The translation of “Bontsha the Silent” is by Hilde Abel, as reprinted in Great Jewish Short Stories, edited by Saul Bellow (Dell, 1963).

~~~~~~~

from the July 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|