|

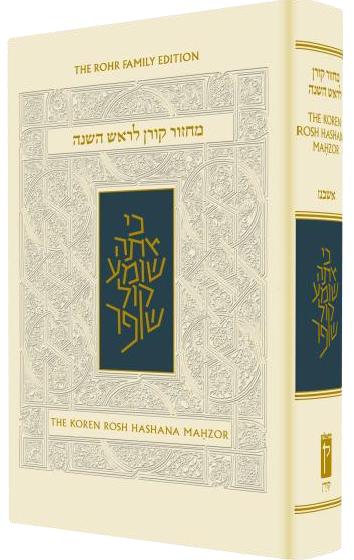

Koren Rosh Hashana Mahzor

Reviewed by Jay Levinson

The Koren Rosh Hashana Mahzor

by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks

Jerusalem: Koren Publishers (2011)

When I first received a pre-publication edition of this Rosh Hashanah Machzor for

review, I was rather dubious about the need for yet another prayer book. My qualms, however, were quickly

allayed. The translation and commentary make a significant contribution to the liturgical literature.

One can always quibble with small details in translation, and this Machzor is no

different. There are fine nuances that might have been expressed using other words. There are words and

phrases that might have been translated otherwise. In general terms, however, the English translation is

quite readable and tones down the stilted and archaic English typical of many religious texts.

The font selection is excellent, providing the reader using Sephardic pronunciation with

the important tool of distinguishing kamatz katan (קמץ קטן) from kamatz gadol

(קמץ גדול) Even the

reader using Ashkenazic pronunciation should appreciate the differentiation between sheva na

(שוא נע) and sheva nach

(שוא נח), as well as patach

(פתח) pronounced before the letter

printed above the vowel..

Some readers might prefer Hebrew on the right-hand page and English to the left. That

is a matter of personal choice, and certainly not a difficult feature to overcome. Perhaps best in the layout is

the inclusion of a Hebrew word or phrase to help “locate” the reader in the English translation.

Frankly, this Machzor is not for everyone, but then again very few books are

appropriate for all. It is written with the Modern Orthodox user in mind, though even the English-speaking

chareidi Jew will benefit from the English translations and explanations of difficult Hebrew,

particularly in some of the piyyutim (poetry).

The inclusion of the prozbul (פרוזבול) (transfer of debts to a religious court) is a welcome innovative addition to the Machzor, but

in keeping with simplicity, only the custom to use prozbul at the end of the Shemitta year is

mentioned; the alternative opinion of use just before Shemitta is not cited.

The commentary cites a wide variety of sources. For example, Rabbi Sacks highlights

the philosophic differences between Greek thought enunciated by Philo and Jewish thinking. As Sacks

explains regarding the Amida, Judaism starts with the universal, then moves to the person-specific.

The universe is the context into which man fits. The Greeks take the opposite tact, first emphasizing the

individual, then building upon him to deduce the universal.

Sacks certainly does use traditional sources, both classic and modern, in his

commentary. For example, regarding Psalm 130 said just before Borchu (ברכו) in the Morning Service, he retells a story in the name of Rabbi Joseph Soleveitchik, who relates

the words of a non-believing Jewish doctor who was in a Latvian concentration camp from which there were

few survivors after the Holocaust. He saw yeshiva students reciting the psalm each night and wished that he

had their faith.

Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav is quoted regarding the daily morning blessings. When we

bless G-d, we are essentially thanking him for his blessings. Every word increases our acknowledgement of

the Al-mighty. “The world is full of the light of G-d, but to see it we must learn to open our eyes.”

Not all is philosophical. Sacks brings the question if a hearing-impaired person using a

listening aid is considered deaf, hence not obligated to listen to the sound of the shofar. He brings

the contrasting opinions of Rabbi E. Waldenberg (commonly associated the Shaarei Tzedek Hospital in

Jerusalem), who rules that this is considered able to hear, and the position of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, who

has a different opinion.

Not to ignore classic sources, ten reasons given by Saadia Gaon (882/892- 942) for the

sounding of the shofar are listed in the commentary. Needless to say, Talmud references and

quotations are ubiquitous.

Sacks’ contributions to the volume are significant. Not only does the selection of others’

comments constitute a substantive editorial role. Sacks also adds material in his own name. His analysis is

keen and unique. In his introduction, for example, he describes the transition from national responsibility

during the First Temple period to individual introspection and repentance (a key part of Rosh Hashanah

today) in the Babylonian Diaspora.

Another example of Sacks’ approach is his interpretation of the Ashrei

(אשרי) prayer before Mincha. He

writes that it is an abbreviation of the morning’s psukei d’zimra (פסוקי דזמרא). It is also a short form

of the Book of Psalms, starting with the first word in Psalms and ending with the last.

There is no doubt that this Machzor makes a significant contribution to religious

literature. Hopefully it will also enrich the Rosh Hashanah experience of those who use it.

~~~~~~~

from the August 2011 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|