Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Goebbels,

Propaganda and Myth

By Peter

Bjel

This is the third and final article

for the first article click here

for the second article click here

The

lack of tolerance for dissent and individuality was central to Joseph

Goebbels’ propaganda. In the pre-war and wartime periods, Nazi

myths and ideals became reality, underpinning and justifying Nazi

policies, their enactment, and eventual wartime conduct. This is the

third, and final installment, of three articles.

Central to the Third

Reich’s propaganda was the lack of tolerance for dissent and

individuality. So much of its pronouncements and rallying-calls

emphasized the collectivism and unity of Germany, often against

ubiquitous internal and outer derision. It culminated in the Second

World War that, not without a hint of irony, Goebbels’ staff

portrayed as a stepping-stone for Germany’s continental and

global ascension, which had been forced on the country by outside

forces and the ‘Jewish-Bolshevik’ influence. In the

geopolitical realm, pre-war and during wartime, myths and ideals

became reality, underpinning and justifying Nazi policies, their

enactment, and eventual wartime conduct.

* * *

The earliest and most

potent myth that came to justify the Nazis’ seizure of power,

but was exploited repeatedly before then for its wide gravity, was

that of the Versailles Treaty and the November 1918 “stab in

the back,” which led to Germany’s economic and

metaphysical ruin. Such early appropriations of subjects for

propaganda and myth making had the added value of being widespread

and not simply confined to the political lunatic fringe of the German

far right. Post-war Germany was “an ideal incubator for a wide

variety of totalitarian myths,” whereby so many politically

atomized Germans turned to the proverbial security blanket of

totalitarian ideology.1

“All versions of the

myth agreed on the reason for the collapse of this almost perfect

society in the First World war. Germany’s military defeat, and

hence the establishment of the despised republic, was not the result

of military setbacks but a consequence of an international Jewish

politico-financial conspiracy.”2

For the fledgling, but

soon emergent National Socialists, this was the proverbial grist to

their mill, and became a staple myth out of which they found

justification. From this emerged the Third Reich’s eventual

pinpointing of enemies, their presence everywhere, constantly

scheming to destabilize and, ultimately, destroy what had been

created.

Joseph Goebbels partook in

this myth making and scapegoat seeking: “Their policy was one

of attack. Attack represented strength….In any situation,

however adverse, aggression was the rule. On one occasion Goebbels

found a policeman had confiscated his car because it was parked in

front of a hotel entrance. He immediately created a scene, lost his

temper and turned the situation into a public exhibition in which he

called the policeman a Communist and began to incite the people

attracted by the shouting against the government. The result of

this, he boasts, was that the police thenceforth left his car

strictly alone. Aggression pays!”3

As such, “The party,

therefore, was constantly being rallied, and enemies created for it

to fight. The enemies were the government, the Communists and the

Jews.”4

Events and individuals

were morphed into epitomized Nazi ideals, often courtesy of Goebbels

himself. On 11 February 1927, at a beer hall in Pharus-Saele,

Berlin, Goebbels undertook to craft an anti-Communist scheme that

would destabilize the movement, confuse observers so as to have them

question their real political allegiances and channelled resentments,

and to also draw blood. As Joachim Fest has written, “His

[Goebbels’] practice of stirring up fights was the logical

application of a new, completely Machiavellian principle of

propaganda. The blood which the party’s rise cost among its

own members was regarded, not as an inevitable sacrifice in the

struggle for a political conviction, but as a deliberate means of

furthering a political agitation which had recognized that blood

always makes the best headlines.”5

Communist

street fighters, like these ones, were a common sight in Germany

during the early 1920s. The Nazis’ routinely set their sights

on the Communists.

According to Viktor

Reimann, Goebbels then proceeded, after this brawl, to try and carry

on his speech, all the while unnamed wounded SA men were dressed and

bandaged on the platform by him. “Almost the whole Berlin

press gave it front-page coverage….He had given the Berliners

their sensation, and the press was full of it. Goebbels and the

NSDAP [Nazi Party] were the talk of the town.”6

Partly out of these pitted

factious battles emerged not only the theme of self-sacrifice, but

also an undermining of individuality – which had also

manifested as one of the targets in Nazi cultural policy (discussed

in an earlier article). On the whole structures and myths of Nazism,

Fest writes “…the whole arsenal of stimulants, developed

with inventive ingenuity, for exciting public ecstasy was ultimately

intended to bring about the individual’s self-annulment, a

permanent state of mindlessness, with the aim of rendering first the

party adherents and later a whole nation totally amenable to the

leaders’ claim to power.”7

Goebbels’ party

organ Der Angriff propagated the ‘fallen SA’ image

as a laudable sacrifice. One such early figure was Ernst Schwartz.

“Now this devout and committed man, a minister’s son, was

the victim of the Communists, who had brutally murdered him. The

example of Schwartz, the editors of Der Angriff hoped, would

contribute to the myth that storm troopers were ordinary men, making

extraordinary sacrifices for the benefit of Germany.”8

In this same fashion, the paramount instance of myth making and

eulogizing of the Nazi ideal was with the legend of Horst Wessel.9

In reality, Wessel had

been an ordinary SA man and labourer, whose love affair with a

prostitute probably earned him the ire of her pimp, who proceeded to

kill him. Nonetheless, Wessel was an identifiable ideal that

Goebbels knew could be very valuable if tweaked and mythologized.

“For Goebbels, it was insufficient to intone chants over the

bodies of countless SA men. He was convinced that generalities do

not move the masses; only easily identifiable symbols would serve

such a purpose. The agony and death of Horst Wessel, killed by

communists in the winter of 1930, was exactly the theme that the

Gauleiter [i.e. Goebbels] needed to offer his propaganda the unifying

symbol it lacked.”10

Wessel, who expired from

his wounds after five agonizing weeks, became the subject of the

“Horst Wessel Song” (or “Die Fahne hoch,”

meaning “The Flag on High”). It was played at numerous

Nazi Party rallies and at any time that Goebbels sought to invoke the

ethos of heroic self-sacrifice for Fuehrer and Vaterland;

eventually, it became the “official ballad of the NSDAP.”11

Horst

Wessel (above) became the focus of a concerted myth of heroism and

self-sacrifice.

In the same time period of

the 1920s that Goebbels first became involved with the Nazi Party,

the movement had been driven underground for reasons of legality and

disunity. It had been divided up into regional branches that often

worked incongruously, instead of synonymously. It was a truly

divided house: “The Nazi movement that Hitler confronted on his

release from Landsberg in December 1924 was in a state of decline and

organizational dissolution.” Having realized that an armed

putsch against the Weimar Republic could only end in failure,

Hitler knew that “the old party with its image of a compact

pseudo-military shock troop was not only anachronistic, but, in view

of Hitler’s probationary release from jail, politically

dangerous.”12

It should also be added that, “In November 1923 the NSDAP did

not have this kind of support: it was not an all-German party, and

its organizational distinction from the rest of the Bavarian folkish

movement was not always clear.”13

Yet, when the advantage

had switched to Hitler, Goebbels and company, reality was wilfully

cloaked by myth and propaganda. This period was later collectively

being referred to in reverence as, again, Kampfzeit, or the

“time of struggle.” Upon his release from

prison, Hitler, at the famous Munich Buergerbraeukeller, invoked “the

past unity of the movement,” but failed to mention his

differences with Erich Ludendorff, his trial and imprisonment, and

declared his ultimate personal responsibility for the course of the

Nazi movement, which won him praise, “enthusiastic applause and

cries of Heil.”14

Goebbels mythologized the

figure of Hitler throughout the Third Reich’s twelve years.

“Goebbels accompanied his doctrinal sermons with incessant

adulation of Hitler. Indeed, this was the most important factor in

the creation of the Hitler myth, the invention of the public figure

of the Fuehrer as distinct from Hitler the private person, and in

making it a force for consensus and national unity, first in the Nazi

movement and later in the Third Reich.”15

Dietrich Orlow intimates

in his analysis that it was after this point in Nazi Party history

that there began to be constructed, by Goebbels and company, the

enduring concept and image of the ‘Hitler myth.’ As he

writes: “After the Buergerbraeukeller speech Hitler moved

quickly to convert emotional acceptance of his personification of the

leader myth into concrete, organizational control of those captured

by his charismatic appeal. His method was simple. In effect, he

deliberately repeated his Buergerbraeukeller performance numerous

times as, throughout the spring and summer, he tirelessly appeared at

party section meetings (that is, gatherings restricted to party

members and their guests) in the city….Through these meetings

Hitler quite literally succeeded in solidifying and formalizing the

effects of his charismatic control devices – oral

communication, handshakes, eye-to-eye contact, and the like –

into the members’ personal subordination to his organizational

leadership. He made rapid progress, moreover, in winning over the

membership.”16

Shortly thereafter, the

myth had grown exponentially: “By the end of 1925 Hitler’s

isolationist tactics, his consistent anti-Semitism, and the

publication of his autobiography had securely established his status

in the south as a super leader who fulfilled and embodied the leader

myth….Hitler’s 1923 Putsch became the culmination

of a series of events that began on August 1, 1914. Hitler was the

personification of the German struggle against all enemies, foreign

and domestic, from 1914 to 1923. He was not only the concrete leader

of the future folkish Germany, but his leadership had also given

meaning to the Reich’s past struggles. He was the

twentieth-century leader of the German people.”17

Goebbels worked actively

to create a generic image of Hitler that could appeal to cross-strata

German society, of all ages, emphasizing the “heroic aspect of

his personality. His portrait was a potpourri with something for

everyone.”18

After the Nazi seizure of power, electoral films – as distinct

from the supervised creative work being churned out by the Ministry

of Culture – were tagging this theme of the Hitler myth.

William G. Chrystal

writes: “Hitler is a man who creates his own economics –

and it works. He creates his own foreign policy – and the

Rhineland returns to the Reich. He creates his new armed forces, and

the allies do nothing to stop him. In short, Hitler does exactly

what he promised he would. The March 29, 1936, plebiscite found 99

percent of the votes in his favor.”19

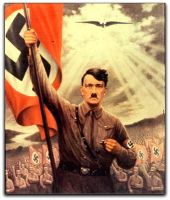

Nazi

propagandists often cast Hitler as a divine-like icon, as this

example shows.

Goebbels was enraptured by

this hallowed Fuehrer, throwing his own cautions and advice to the

wind, even at times as when during the war, real defeat began to loom

on Germany. After the 20 July 1944 Army bomb plot attempt against

Hitler, Goebbels attributed Hitler’s survival to something akin

to Divine Providence.20

The myth was not altogether phoniness, given that Hitler was

extremely lucky in this particular attempt on his life, but it

resonated among many ordinary Germans: “Accordingly it was

women in particular who worshipped him, who fell into ecstasies when

they saw him in person, who even set up a ‘Fuehrer niche’

in their living rooms, with flowers and his picture, in place of the

little religious shrine they would previously have had….In the

eyes of many Germans, Hitler, as a substitute for God, stood above

earthly concerns.”21

In the course of the

Second World War, the Nazis, in their supreme confidence in total and

absolute victory through war, conquest and territorial expansionism,

eventually found themselves seriously overdrawn. It was logical

that, in the winter of 1942-1943, the shattering defeats at the

Battles of Stalingrad and El Alamein shifted the course of the war

against them. For Goebbels, this was an ideological challenge, as

much as it was a practical one, of reconciling a decisive defeat –

specifically at Stalingrad – with the all-purveying myth of

Nazi invincibility.

Hitler himself partook in

this saving-face even before the spectre of defeat loomed on Germany,

instructing journalists that, “Instead of stressing the capture

of localities in and around Stalingrad, they were to emphasize the

bitterness of the fighting and the bravery of the German soldier.

Stalingrad was to be referred to as a fortress which had to be

stormed; if the campaign slowed down, the strength of the Soviet

fortifications would serve as a ready excuse.”22

In late October 1942, the

SS paper Das Schwarze Korps portrayed the Soviet Red Army’s

resilience and strength in racial and bestial terms. “The

Bolsheviks on the other hand refused to realize when a struggle was

useless, and continued to fight to the last man. Thus Stalingrad

represented the quintessence of the Soviet contempt for the human

race.”23

When the freezing cold defeat did become clear, Hitler gave Goebbels

permission to disclose this truth, but to keep dramatizing “the

heroism and self-sacrifice of the men at Stalingrad in order to urge

a more dedicated war effort on the German home front,” and that

“An entire Army had sacrificed itself ‘for all of us,’

and indeed, for western civilization. Goethe and Beethoven, Augustus

and Pericles were being defended in the wilds of the East.”24

It was saving face, in light of military disaster, through the craft

of myth making.25

Only as the war came home

to the Third Reich’s capital did the edifice of propaganda,

myth and illusion, honed and constructed wilfully by Goebbels, begin

to fall apart like a row of dominoes. When, in April 1945, this

apparatus fell apart, its parent regime’s fate was not long in

following. After the 20 July bomb plot on Hitler, Goebbels finally

was given the title Minister for Total War. Even in his

time-honoured capacity for delivering the tasks Hitler so demanded,

the war made his new portfolio completely useless, but for delaying

the inevitable for a few months’ longer.

In the same fashion as the

Horst Wessel sacrifice, Goebbels justified the destruction of Germany

brought on by Hitler’s policies – now a target, after

1943 especially, of routine Allied carpet bombings – by first

promising retaliation, or Vergeltung, which became a staple of

his propaganda after 1943. It then began dying out for its

incongruity, laughable mythologizing of the V-1 and V-2 rockets’

effectiveness, “Unrestrained exaggeration and downright

dishonesty…”26

When this promise fell through, he seized on faith in Hitler, and in

the spirit of resistance: “But for us it has always been a

fixed and immutable principle that the word capitulation does not

exist in our vocabulary!…We have faith in victory because we

have the Fuehrer!…Faith can move mountains! This

mountain-moving faith must fill our hearts!”27

A photo

of the V-2 rocket, sometime in 1945. Goebbels attempted to

mythologize the V-2 capability in the final period of World War II.

“By 1944 Goebbels

was making propaganda as much for himself and the leadership as for

the masses: It was a consolation in the midst of despair and

destruction.”28

In the final weeks of April 1945, Goebbels tried to make the most

out of the groups of resistance fighters, known as ‘Werewolves,’

defending the Reich capital and executing any pacifists or defeatists

that they found, but like Hitler’s strategic scope, the reality

was actually sorrier than the figures on paper.29

Thus, unity, myth,

ubiquitous enemies and war came to underpin, by Goebbels’

machinations, the scope of Nazi geopolitics, stretching from the

period of Hitler’s release from prison, to the final days of

the Third Reich. In its essence, it was a phenomenon that involved

making real that which was not, and vice-versa, in the underpinning

of Nazi geopolitical conduct and function.

In his desperation and

secluded isolation, awaiting the moment that he would be deported to

a dark but uncertain place, Victor Klemperer, an academic before the

war (and a Jew by birth, who later became a Protestant), meticulously

kept a diary that fulfilled his own need to resist Hitler the only

way that he could. At the risk of death if discovered, he also

chronicled in its pages how he secretly worked on a manuscript

entitled LTI (Lingua tertii imperii), dealing with

language usage and the deliberate, common literary and figurative

metamorphoses taking place at the hands of the Nazis, transforming,

for example, words ordinarily denoting vices into Nazi-extolled

virtues. Essentially, Klemperer documented the constant and wilful

twisting of reality taking place around him. The all-pervasive

presence of Goebbels figures throughout his diary from 1942-1945.30

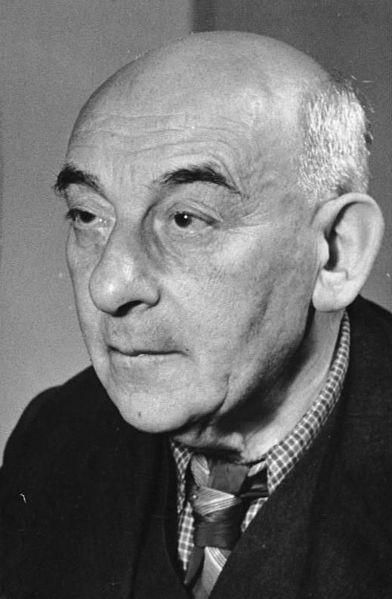

Victor

Klemperer, circa 1952

Klemperer was one of the

lucky Jews (irrespective of how he viewed himself) to survive the

Third Reich. So many others did not, whose forced emigration and,

eventually, isolation, vulnerability and murder were spurred on and

justified in no small measure by Goebbels’ own opportunistic

anti-Semitism and propaganda, which held out even though it proved to

be a shaky foundation in the Third Reich’s dying days. “All

his attempts to paint the universal enemy as a wirepuller at work

from Moscow to Wall Street were shattered by the reality of the

frightened and harassed human beings wearing the yellow star, who for

a time wandered the streets of German cities before suddenly

vanishing forever.”31

Consistently vilified and

vilely demonized in propaganda, popular culture, official ideology,

the November 1938 Kristallnacht pogroms, and foreign policy

(the Nazis’ other war), the image of ‘Der Ewige Jude,’

the ‘Eternal Jew,’ to not speak of the boosts provided by

the film of the same name, led straight to the “Final

Solution.” This was the culmination and ultimate price paid by

Goebbels’ misanthropy-turned-opportunism.

***

As Nazi propaganda was born by Goebbels,

so too did it die with him. His final days were spent in Berlin,

where he partook in the Reich Chancellery bunker’s macabre

final events that characterized the end of the Third Reich. Up to

the very end, he and his dwindling number of staffers had kept

churning out radio broadcasts and editorials in Das Reich,

glorifying and edifying self-sacrifice, heroic resistance, and

perseverance to a time when war, the conglomerate of international

Jewry and Bolshevism would be a thing of the past, the Greater German

Reich resurrected, and the Fuehrer back to where he rightfully began

his unfinished mandate.

Goebbels and his six

children. He and his wife poisoned them before aving themselves shot

outside Hitler’s bunker on the evening of 1 May 1945.

His last article in Das Reich was,

predictably, entitled “Resistance at Any Cost,” and the

only factor that stopped him from propagating it was because the

paper could not be distributed.32

Along with his wife and six children, he joined Hitler and the

remaining Nazi entourage in the bunker beneath the wrecked

Chancellery, where Goebbels partook in Hitler’s final birthday

celebration on 20 April and, nine days later, was a formal witness to

his marriage to Eva Bruan, and co-signed his last will and testament.

Two days later, on the evening of 1 May, Goebbels mimicked Hitler’s

conduct by having himself and his wife shot by an SS orderly –

but not before they had their six children poisoned as they slept.33

To restate matters, the uses of ubiquitous

propaganda were crucial for Nazi rule; Nazi propaganda was a

masquerade and disseminator of Nazi ideology, without which the

events and manifestations emanating from the Third Reich could not

have happened. The scope and unprecedented apparatus of the Nazi

system of propaganda distinctively owed its genesis to Goebbels, who

crucially went about creatively and subtly disseminating the Nazi

ethos via cultural routes. There were scarcely any remaining

cultural avenues left that had not been touched by him. To underpin

Nazi geopolitics, and all the policies that figured from this realm,

propaganda and the creation of myths transformed the unreal into

reality and justified Nazi policies and conduct; when warfare came

smashing into the centre of the Third Reich, so too was Goebbels’

system smashed.

On the surface, it is hard

to believe that so much of the Nazi phenomenon owes its manifestation

to Goebbels. While it did not emanate solely from him, he was the

link, the “practitioner and technician” of totalitarian

rule that Hitler seized upon to carry forth Nazism. “Until he

discovered Hitler, he [Goebbels] lived in a void, clutching at

changing ideologies, feeding on nihilism and resentment.”34

The negativity lingered on well past his discovery of Hitler and

Nazism; the legacies of this still live.

* * * * *

- Peter Bjel is a

freelance writer and teacher candidate, and holds degrees in Politics

and History from the University of Toronto. He can be reached at

peterbjel@hotmail.com.

This is the final third of three articles about Goebbels, propaganda

and the Third Reich.

NOTES:

1

Dietrich Orlow, “The Conversion of Myths into Political Power:

The Case of the Nazi Party, 1925-1926.” The American

Historical Review 72, 3 (April 1967): pp. 906-924, at pp.

906-907.

3

Roger Manvell and Heinrich Fraenkel, Dr. Goebbels: His Life and

Death (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960), p. 107.

5

Joachim C. Fest, The Face of the Third Reich (New York:

Pantheon Books, 1970), p. 90.

6

Viktor Reimann, Goebbels: The Man Who Created Hitler (Garden

City, NY: Doubleday, 1976), pp. 76-77. He adds: “Goebbels’

conquest of Berlin began with the battle in the Pharus-Saele. He

had become known, he had gathered the activist party members around

him, he had strengthened their fighting morale and whetted their

aggressive appetites. They had tasted blood” (p. 77).

7

Fest, The Face of the Third Reich, p. 83.

8

Russell Lemmons, Goebbels and ‘Der Angriff’

(Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1994), p. 67.

9

For full accounts of the Wessel affair, the details and motives

behind his murder, and its conversion to Nazi myth, see Ibid., pp.

71-75; Reimann, Goebbels, p. 117; and Ralf Georg Reuth,

Goebbels: A Biography (New York: Harcourt Brace &

Company, 1993), pp. 110-113.

10

Jay W. Baird, “Goebbels, Horst Wessel, and the Myth of

Resurrection and Return.” Journal of Contemporary History

17, 4 (October 1982): pp. 633-650, at p. 634.

11

Lemmons, Goebbels and ‘Der Angriff,’ pp. 71-72.

For more on the myth and its manifestations, see Baird, “Goebbels,

Horst Wessel, and the Myth of Resurrection and Return.”

12

Orlow, “The Conversion of Myths into Political Power,”

p. 910.

14

Ibid., pp. 912-913, for details.

15

Gordon A. Craig, “The True Believer.” New York Review

of Books 41, 6 (24 March 1994), HTML.

16

Orlow, “The Conversion of Myths into Political Power,”

p. 913.

18

Herzstein, The War that Hitler Won, p. 54.

19

Chrystal, “Nazi Party Election Films,” p. 43.

20

Reuth, Goebbels, p. 333, on the pseudo-religious portrayal of

Hitler’s survival. On throwing caution to the wind, see pp.

291-292, for example. See also Reimann, Goebbels, pp.

294-295.

21

Ibid., p. 232. The literature on the 20 July 1944 attempt on

Hitler’s life, and on the German Resistance itself, is growing

steadily. A good start – by this author’s

recommendation – is Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler’s

Death: The Story of the German Resistance (New York: Owl Books,

1997). It chronicles not only the circumstances leading to 20 July,

but tells the story of the German Resistance from the beginning –

including its broader failures and constant ineptness to stop Hitler

and the Nazis.

22

Jay W. Baird, “The Myth of Stalingrad.” Journal of

Contemporary History 4, 3 (July 1969): pp. 187-204, at p. 189.

25

Baird writes: “Hitler and Goebbels realized that the

propaganda coverage of the disaster had to be treated in an

extraordinary fashion. Neither factual reporting nor traditional

misrepresentation would serve their purpose, and they decided that

the sacrifice along the Volga could be explained only by way of a

myth. Reality was thus to be reinterpreted” (Ibid., pp.

197-198).

26

See Gerald Kirwin, “Waiting for Retaliation: A Study in Nazi

Propaganda Behaviour and German Civilian Morale.” Journal

of Contemporary History 16, 3 (July 1981):

pp. 565-583, at pp. 566, 576, 579, for these points.

27

Quoted in Reuth, Goebbels, p. 313.

28

Robert E. Herzstein, The War that Hitler Won: The Most Infamous

Propaganda Campaign in History (New York: G.P. Putnam’s

Sons, 1978), p. 107.

29

Manvell and Fraenkel, Dr. Goebbels, p. 252, on details of the

‘Werewolf’ propaganda.

30

See Victor Klemperer, I Will Bear Witness, 1942-1945: A Diary of

the Nazi Years (New York: Modern Library, 2001).

31

Fest, The Face of the Third Reich, p. 94.

32

On this, see Reuth, Goebbels, p. 355.

33

See H. R. Trevor-Roper, The Last Days of Hitler (New York:

Macmillan Company, 1947), pp. 212-214, on the description of the

Goebbels’ deaths. A more recent analysis of those final days

is Joachim Fest, Inside Hitler’s Bunker: The Last Days of

the Third Reich (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2004),

pp. 141-146 (for the death of Goebbels).

34

Hugh Trevor-Roper, “Hitler’s Impresario.” New

York Review of Books 25, 9 (1 June 1978), HTML.

~~~~~~~

from the December 2011 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used.

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|