That Son-of-a-Bitch Hitler

By Gerry Holzman

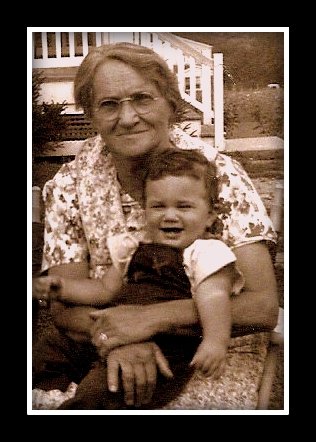

I called her Mama Sarah.

She was my

mother’s mother and she lived with us, on and off, for the

last 15 years of her life. Almost as soon as I could walk, she would

take me on her regular weekly shopping expeditions to help her

confront Jake the Butcher and Abe the Grocer. My short-term payoff

for softening their hard hearts was usually a slice of salami or a

schtickle pickle. The long-term reward was

a trip to the Saturday matinee at the Carlton Theater to watch Tarzan

or Tom Mix.

Because the

feature film was accompanied by a short, a cartoon, and an endless

serial, Mama Sarah always bought a little something for us to eat.

Should her favorite daughter’s only

child go three hours without

food ?

These Saturday

excursions would often begin with a visit to the candy store—the

one with the big wooden Indian by the door—where she would

patiently wait while I made the agonizing decisions required by the

responsibility of picking out a nickel’s worth of candy that

would please both of us. Other times she would stop at the corner

grocery where Abe would fuss over me while he cut us an enormous

slice of halavah from the big round loaf atop the counter.

Every once in a while, she would bring a paper bag from our apartment

filled with taglach or some other Russian treat from the Old

Country. One time, she even brought two thick slices of pumpernickel

slathered with great gobs of yellow schmaltz, an East

European “delicacy” that has been blamed for killing more

Jews than the Russian Cossacks.

Although she

never talked to me about Russia and rarely even mentioned it by

name, Old Country was a phrase that frequently made its way

into her sentences of broken English. It was, “ Jerilah,

bring the alte knoz, from the Old Country,” or “You

want to sleep mit mine Old Country pillow?” or “Such

a snow, like in the Old Country.”

Her family had

come to America in 1898, refugees from the pogroms, the poverty and

the prejudice that were so much a part of Nicholas II’s Russia.

She was Sarah Bernstein then, one of four unmarried daughters of my

great grandparents, two faceless and, I guess, courageous people

about whom I wish I knew something.

It wasn’t

long after her arrival that she met Jacob Lopinsky who was a

shopkeeper on New York’s lower East Side. Overcoming her

family’s groundless concern that he might be Polish (“With

a name like Lubansky, what else!”) she married him and, in

rapid succession, produced three daughters and a son. Seeking a

better life, Jacob Lopinsky moved his family to Madison, West

Virginia where, for 12 years, he conducted a prosperous dry goods

business. Unfortunately, his premature death forced Mama Sarah and

her adult children to leave and return to New York City. Because she

had no marketable skills, she was entirely dependent upon her meager

savings and the compassion of her children.

So that is how

she came to live with us, first in a Jewish neighborhood in Jamaica

and then, shortly after my father opened a department store in

upstate New York, in our new home in rural Amenia.

She arrived along

with a large steamer trunk which contained all of her important

possessions, many of them the very same items that her family had

originally brought from the Old Country: the large dented brass

samovar, two complete sets of dishes, pots and silverware--one for

meat and one for dairy-- down pillows, a huge quilt, linens, and an

odd assortment of silver wine cups and brass candlesticks.

I don’t

recall her bringing any books or for that matter, ever seeing her

reading one. I know she could not read or write English; although I

am fairly certain she could read some Yiddish since the occasional

visitor from New York City would sometimes bring a copy of the Daily

Forward for her.

Nor did she bring

any photographs. I would not have expected to see many from Russia

but as I look back, I’m surprised that there were none from the

Lower East Side days or the West Virginia years. She literally had

nothing tangible to look back upon.

Simply put, other

than a few pieces of cloth, the only physical connections to the Old

Country and to her past life in America were items used to prepare

and serve food.

Fress a

bistle, Jerilah,” she would constantly

urge me as she hobbled around our tiny kitchen in Amenia, preparing

some aromatic concoction from the Old Country. Although she spoke

to me mainly in heavily accented English, she sprinkled her sentences

with large doses of Yiddish. I never, ever spoke Yiddish to her or

to anybody else—it was beneath the dignity of a teen-age

American boy to speak such an alien and shameful language in the

1940’s—but I understood nearly everything she said.

“ Furstaist vus er zug der?” (Do

you understand what I am saying to you?) she

would sometimes challenge me and I would invariably nod or mumble

affirmatively.

In truth, Food

was our common language, our mother tongue, our mama lukshon.

Because there were no photographs, no books, no art work, no--not

even a bubamiesah or two—it was through the medium of

food that she taught me about the Old Country; the range of her

course offerings was enormous: stuffed derma, fried herring and

pickled herring, borscht and blintzes, gefelte fish ( for this, she

grew her own horse radish), matzoh brie, chopped liver, honey cake,

mandelbrot, knishes, challah…

To this day, I

love the music--the pulse and the cadence--of the names of these

traditional Yiddish delicacies nearly as much as I love their taste

and smell:

kugel, gribenitz, kreplach,--

kishka, tzimmes, knaidelach—

latkes, schmaltz, and

taiglach.

One might even

say that Mama Sarah was a minstrel of sorts; her lyre was the stove

and her song was “Fress a bissel.”

But the minstrel

too early lost her lyre and her song too soon came to a close.

During the last

three years of her life, she was forced to drastically curtail her

activities because of a very severe arthritic condition. The

stiffness in her hands and legs became so extreme that she could not

even work in her beloved kitchen. There were to be no more sallies

to joust with Jake the Butcher nor onions to be chopped with the alte

knoz. Mama Sarah’s world was reduced to her bedroom(which

I shared with her) and a daily fifteen-foot journey into the living

room. The radio became her principal source of entertainment,

information and social stimulation.

She loved Stella

Dallas, the wise Kitchen Table Lady whose adventures opened the

afternoon soap opera schedule (“a real bahlahbustah”);

she laughed at the escapades of Lorenzo Jones, the amiable inventor

(“some schlemeil’); and how she detested Our Gal

Sunday’s snobbish husband, Lord Henry Brinston (“a

regular Cossack”).

Those radio years

were the years of World War II so Mama Sarah listened faithfully to

the Sunday evening broadcasts of Walter Winchell (“a

gantsheh kibitzer”) and expressed enormous admiration for

President Roosevelt (“such a mensch”). But she

saved her strongest emotions for Adolph Hitler (“He should

gai in drerd, that son-of-a-bitch Hitler.”) For Mama

Sarah, he was never Adolph Hitler, he was always “That

son-a-bitch Hitler.”

The German tyrant

was never far from her thoughts. Each morning as she endured her

heartbreaking journey from bedroom to living room, leaning heavily on

her cane during each agonizing step, she would invariably pause along

the way to mutter a curse, “That son-of-a-bitch Hitler, he

should have what I have.” Once Mama Sarah had finished

telling God how to deal with Hitler, she would take a couple more

short steps and collapse into her stuffed chair, ready to exist for

another day.

Mama Sarah died

in the early fall of 1946. She outlived that son-of-a-bitch Hitler

by more than a year.

~~~~~~~

from the June 2012 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used.

|