| |

April 2013 |

|

| Browse our

|

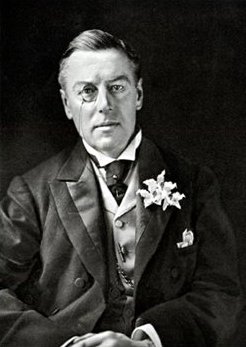

Joseph Chamberlain

A Refuge for the Night: Reviewed by Jack L. Schwartzwald African Zion

The Balfour Declaration of 1917, pledging the British Government’s support for “the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people,” is a well-known milestone in the rebirth of Israel. Less well known is the fact that the Balfour Declaration was not the first, but the second British offer to assist the Jews in the creation of a Jewish homeland. African Zion (347 pp., Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1968) by Robert G. Weisbord, Professor emeritus of History at the University of Rhode Island, remains the sole book-length exposition of Britain’s first offer—an exotic scheme to create a Jewish colony on the Uasin Gishu Plateau in what is today western Kenya. With two hundred and fifty-nine pages of text and seventy-six more of notes and references, Professor Weisbord’s work is the essence of scholarship—indeed, it was initially written as his doctoral dissertation at New York University—yet it reads with the ease of a novel. When asked recently how much of the dissertation text had to be revised before the manuscript was accepted for general publication, Weisbord replied, “Not a word.” (The letter of acceptance, incidentally, came from the Jewish Publication Society’s Chaim Potok, famed author of The Chosen.) Weisbord’s topic is the stuff of literature, running the gamut from benevolent Christian Zionism to anti-Semitism and from backroom political machinations to African exploration. Along the way, Weisbord debunks the myths and misconceptions that surrounded the project, and that, in many cases, remain all that is “known” by amateur authorities. Not the least of these is the story of how a land offer in Kenya was, for decades afterward, mistakenly dubbed the “Uganda” proposal (and in many cases is still so called today). Writing in 1945, the Zionist historian Israel Cohen posited that because the name “Uganda” was virtually synonymous with “the wilds of Africa,” those opposed to the project labeled it the “Uganda Scheme” as a term of derision.1 But there was also genuine confusion on the issue for which Weisbord has uncovered a geographical explanation. At the dawn of the 20th century, Uganda and the “East Africa Protectorate” (later Kenya) together comprised a contiguous stretch of territory that was more generally referred to as “British East Africa.” Of these two component parts, Uganda possessed the more intriguing name and a far more celebrated history of exploration. The name “Uganda” thus became synonymous with both territories in the popular mind—so much so that when the British government invested 5.25 million pounds sterling in the risky venture of constructing a railroad across Kenya, it came to be called the “Uganda” Railway, even though not one inch of it was actually located in that country.2 The Uasin Gishu Plateau offer was the brainchild of then British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, who had already had several meetings with Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, regarding possible settlement sites for the Jews in British colonial territory. Chief among these sites had been El Arish (in the Sinai Peninsula) and the island of Cyprus—both near to Palestine geographically. For various reasons, these possibilities proved untenable. But in viewing the Kenyan countryside from the Uganda Railway during a 1902 visit, the idea struck Chamberlain that this was “just the country for Dr. Herzl.”3 In due course, a formal offer was transmitted to the Sixth World Zionist Congress (held in Basle, Switzerland in August 1903), in the form of a letter from Sir Clement Hill at the British Foreign Office to Zionist notable, Leopold Greenberg, in London. Whatever may be said of the scheme, it was something more than half-baked at the time it was presented. The British went so far as to prepare a draft colonial charter (written coincidentally by David Lloyd George, who was to be Prime Minister at the time of the Balfour Declaration) that included a tentative name for the colony: “New Palestine.” Britain’s generous proposal bade fair to fracture the Zionist movement in two—pitting those who saw the opportunity as a “nachtasyl” or “refuge for the night” for Eastern Europe’s persecuted Jewry against those who regarded any consideration of the offer as a betrayal of the fundamental goal of Zionism: i.e., the creation of “a publicly recognized, legally secured home in Palestine for the Jewish people.” Although the Zionist Congress ultimately voted 295-178 to send a commission to study the proffered territory, the decision was not finalized until Herzl convinced the large delegation from Russia, which had stormed out of the proceedings in protest and despair, to return to the assembly hall. (Russian Jewry at the time was the most vulnerable in Europe, and yet the most opposed to the proposal. Herzl was so taken aback by the Russian delegation’s temporary secession that he exclaimed to several colleagues, “These people have a rope around their necks, and still they refuse.”4 In a bizarre sequel four months later, a deranged Russian Zionist fired a pistol at Herzl’s longtime associate, Max Nordau, crying, “Death to Nordau, the East African!” Nordau survived without injury, but a man standing next to him was wounded.5)

As it turns out, Russian Zionists were not the only people who stood in opposition to the project. The white settlers already resident in Kenya wanted to see the population grow, but they had in mind immigrants of a higher social class than the “alien Jewish paupers” who were likely to flow in from Eastern Europe. The alarm was sounded that Kenya would become “a Foreign State under British protection.”6 The Jews were stereotyped as being poor agriculturalists (a contention that was even then being disproved by the successful agricultural settlements that Jewish pioneers had established in Turkish Palestine) and as swindlers who were likely to take advantage of the natives. Researching in the African Standard newspaper, Professor Weisbord uncovered attacks that were even less nuanced in their anti-Semitism, including an editorial entitled, “Jewganda,” and a business advertisement, which read, “East Africa may be Jewed, but you will not be if you deal with T. A. Wood, Nairobi Stores.”7 Such opposition, compounded by financial constraints and the unexpected death of Theodor Herzl, served to delay the Zionist Congress’ investigatory commission for more than a year. When it finally put in at Mombasa in January 1905, it consisted of three men, the well-known African explorer Major A. St. Hill Gibbons; the scientist and trekker, Professor Alfred Kaiser; and a certain N. Wilbusch, the only Jew among the three. The purported adventures of this trio in Kenyan territory gave rise to a myth that would live for decades. As the story goes, two white settlers offered to join the commission in its travels for the secret purpose of sabotaging the inquiry. The alleged results were the pitching of tents in an area where lions were wont to roar at night, a close encounter with a herd of rambunctious elephants and the surrounding of the camp by a seemingly angry crowd of spear-bearing Masai warriors. The story was so well known and long-lived that in writing his Middle East Diary in 1959, British intelligence officer, Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, reiterated it, saying “what with elephants by day and lions by night, together with an encounter with Masai warriors in full war regalia, [the commissioners] decided that Kenya was no place for Russian Jewry.”8 (Meinertzhagen, later an ardent Zionist, had been serving with the King’s African Rifles in Kenya at the time of the commission’s visit, and even so had been fooled by the rumors.) In researching the commission’s official report for his dissertation in 1965, Professor Weisbord could find no mention of close calls with lions, elephants, Masai warriors, or for that matter, with the two white settlers who supposedly joined the mission. It so happened that N. Wilbusch was still alive and residing in Haifa at the time of Weisbord’s research and, in correspondence, solved the mystery by noting that none of these encounters had ever occurred. It was all a myth. The commission’s negative report derived not from dangerous adventures and secret conspiracies, but from perceived deficiencies in the size of the reserved territory, and its seeming unsuitability for extensive agriculture. (In fact, the commissioners misjudged on the second point, for the Uasin Gishu Plateau is a bustling agricultural area today). By the time the commission’s report reached London, the East Africa Protectorate had been transferred from the Foreign Office to the Colonial Office, and the latter wanted out of the bargain. The offer to the Jews had raised awareness of the protectorate’s desirability and the Colonial Office now had more applications for settlement from British subjects than it knew what to do with. Similarly, the World Zionist Congress had come to believe that acceptance of the Kenya offer might jeopardize the possibility of ever attaining Palestine. Thus to the relief of both sides, the Seventh Zionist Congress, which met in Basle in July 1905, passed a motion that in Weisbord’s words rejected “either as an end or as a means all colonizing activity outside Palestine and its adjacent lands….”9 (It is a matter of some irony that the Congress would make such a declaration in 1905, since in the same year the British Parliament passed an Aliens Bill, restricting the immigration of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe to Great Britain proper. The confluence of events provoked a new faction—the so-called ITO or “Jewish Territorial Organization”—to split from mainstream Zionism with the goal of establishing a Jewish homeland wherever one might be obtained in order to provide a refuge for Eastern Europe’s beleaguered Jews.)

In 1906, Arthur Balfour who had been Britain’s Prime Minister at the time of the Kenya offer sought the opinion of Chaim Weizmann, a Russian-born Jewish chemist then working in Manchester, England, as to why so many Jews had opposed it—particularly those in Russia whose very lives were at stake. Recalling the meeting in his memoir, Weizmann (who was to become modern Israel’s first president) wrote that Jewish heritage had been tied to Palestine since time immemorial. The land God showed to Abraham was Palestine. Hence, “any deflection from Palestine was—well, a form of idolatry.” He added that, “if Moses had come into the sixth Zionist Congress when it was adopting the resolution in favor of the Commission for Uganda [sic], he would surely have broken the tablets once again.”10 Balfour was unconvinced, citing the immediate need for a refuge for Eastern Europe’s long-suffering Jews. But the exchange of three sentences settled the issue: “ Mr. Balfour,” Weizmann inquired, “Suppose I was to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?” “ But we have London,” Balfour protested. “ Yes,” countered Weizmann, “but we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh.”11 It is something more than a footnote to this story that Weizmann later created a means of synthesizing acetone, thereby rescuing the British armaments industry from a critical shortage of that essential chemical at the height of World War I. According to David Lloyd George, the Balfour Declaration sprung in part from a desire to thank Weizmann for his contribution.

Although the Seventh World Zionist Congress officially declined the Uasin Gishu Plateau offer, the British gesture nevertheless constituted a milestone only modestly less important to modern Zionism than Balfour’s famous declaration. For, in making the offer, Great Britain not only made a benevolent gesture towards a hard-pressed minority, but also formally recognized the Jews as a people. In so doing, the British government had crossed a Rubicon of sorts: Henceforward, in political circles, the Jews were no longer viewed solely as the adherents of a religion, but as a people, just as the Zionist movement held them to be. In the end, both sides gained from this oft-forgotten and always underestimated episode in Zionist history. In writing the only book-length study on the topic, Weisbord has filled a glaring lacuna in Zionist historiography. African Zion has lost none of its value in the forty-four years since its publication, and will remain vital as long as modern Israel perseveres. Jack Schwartzwald is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine at Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School and the author of “Nine Lives of Israel” (McFarland, 2012).

1 Israel Cohen, The Zionist Movement. London: Frederick J. Muller, 1945, p. 80.

2 Weisbord, pp. 9-11. There were other reasons as well, which Weisbord investigates with the eye of a detective, but this one seems most vital to the popular misconception.

3 Howard M. Sachar, A History of Israel from the Rise of Zionism to Our Time. 3rd Edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007, p. 59.

4 Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1949, volume 1, p. 87. Quoted in Weisbord, p. 147.

5 Alex Bein, Theodor Herzl. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1942, pp. 485-6. (The assassin’s cry is also quoted in Weisbord, pp. 143-4.)

6 The African Standard, September 5, 1903, p. 5. Quoted in Weisbord, p. 83.

7 The African Standard, October 24, 1903, p. 1. Quoted in Weisbord, p. 94.

8 Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, Middle East Diary, 1917 to 1956. London: The Cresset Press, 1959, p. 2.

9 Weisbord, p. 223.

10 Weizmann, vol. 1, p. 110.

11 Weizmann, vol. 1, pp. 110-11.

from the April 2013 Edition of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |