| |

2015 |

|

| Browse our

|

Leo Frank Lynching -August 17, 1915

The Lynching of Leo Frank

By Jerry Klinger "Semper Idem"[1]

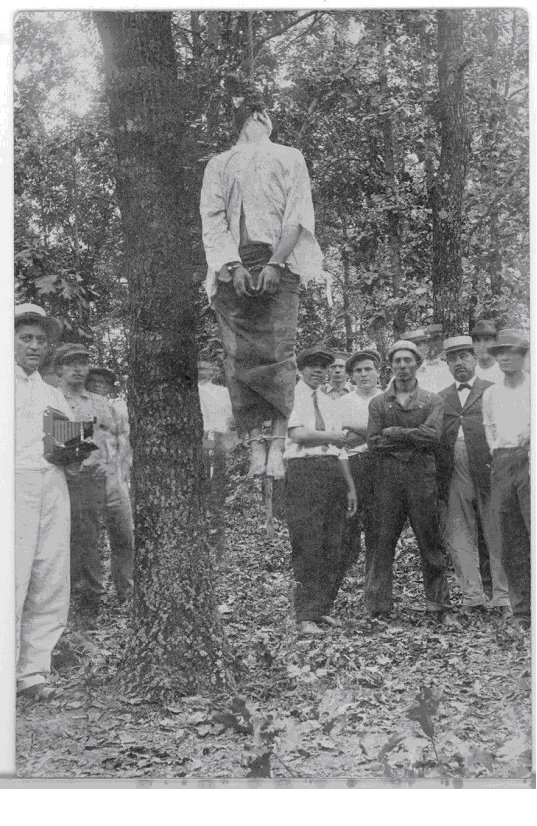

Leo M. Frank There still was fifteen minutes before I could pick up my granddaughter at one of Washington, D.C.'s largest synagogues. She was attending Sunday school. With time to wait, I went into the large synagogue library and asked the librarian if they had any books on Leo Frank. "Leo Who? " She looked at me quizzically. 'Who was Leo Frank? Why is he important? " was the innocent, telling response. "August is the 100th anniversary of the most traumatic event in American Jewish history, the Lynching of Atlanta Jewish businessman, Leo Frank", I answered. The librarian just looked blank. A flicker of life came in to her. Perhaps, it was because of a look on my face. She checked the library catalogue for something among the thousands of books on the shelves. We marched over to the American Jewish history section. They did not have a single book on Leo Frank. The single most controversial, most written about dramatic story of Jewish life in the South, and they did not have a single book. I was astonished but held back any comment. "If you think it important, please write out the name of the subject and an author. We will submit it to our synagogue library committee for consideration and possible purchase for our library," the librarian answered. I wrote out on a slip of paper, that the librarian most likely "lost", the name of a highly respected recent work on the Lynching of Leo Frank, "And the Dead Shall Rise" by Steve Oney. My fifteen minutes was up, I had to get my granddaughter. ~~~~ A few moments before Leo Frank was lynched from a tree on Frey's Gin Road, in Marietta, Georgia, he asked that his wedding ring be given to his wife Lucille. The lynchers were respectable men. Some of them were the finest men of Georgia, Judges, businessmen, officers of the law, even a former Governor. The simple gold ring was slipped from Leo's hand. As promised, it was eventually given to his widow. Leo was hung. Pictures were taken. Thousands of copies of the famous photograph of Leo Frank hanging from a tree were sold as souvenir postcards for many years in Georgia. The lynchers, the onlookers, were satisfied that justice, though delayed, was justice finally done. None were tried for the murder they had done. ~~~ Leo Max Frank was born April 17, 1884 in Cuero, Texas. His family were German Jewish immigrants. His father, Rudolph Frank, had secured a job as postmaster general of the tiny, remote Texas community. Leo was only three months old when the Franks decided that the frontier experience was not for them. After three years living in Cuero, they moved back to Brooklyn where they had come from. Leo grew up in relative middle class comfort. He attended public school and graduated from the prestigious Pratt Institute in 1902. He continued on to Cornell University, studying mechanical engineering. His family was active in the German Jewish community and in the synagogue. However, it was his Uncle, Moses Frank, Rudolph's older brother, who was the head of the family. Moses had become quite wealthy with numerous financial interests in New York and Atlanta. Moses Frank made his fortune as a cotton speculator, but prudently diversified his financial assets. He became a major stockholder in Atlanta's National Pencil Factory. Business relationships were often tribal and preferentially familial. One year after graduating from Cornell, Moses offered his nephew a job managing the National Pencil Factory, once Leo completed an apprenticeship in pencil manufacturing at the Eberhard Faber in Bavaria. Leo spent nine months in Germany learning before becoming the superintendent of the National Pencil Factory in September 1908. He was 24. Leo Frank was quickly inserted into the upper crust of Atlanta's Jewish life. He was introduced to Lucille Selig, herself the daughter of well established, wealthy Atlanta Jews. Her family was among the founders of Atlanta's first Jewish house of worship in 1867, later known simply as the Temple[3], a bastion of Reform Judaism. November 1910, Leo and Lucille were married by the Temple's radical Reform Rabbi, David Marx.[4] Marx assumed the Rabbinic leadership of the Temple in 1898. He energetically tried to assimilate the Temple's community into American life, even substituting Sunday as the Jewish Sabbath. In later years, he helped found the virulently anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism. His efforts created significant tension between the older German Jewish community and the recently arrived, more traditional, Jews from Europe. Yom Kippur 1945, the Holocaust was over. 6,000,000 Jews had been murdered for being Jewish. Rabbi Marx aggressively preached why a possible future Jewish State should not be recognized. He was challenged by angry Congregants during his sermon. The reality of the Holocaust, Rabbi Marx's advancing age and his 51 year Rabbinic leadership of the Temple would soon contribute to his retirement in 1946. His successors reversed the Temple's long time animus to Jewish Nationalism and turned the Temple community's expression of Judaic principles to social activism. 1958, the Temple was bombed, in a vicious anti-Semitic attack, because of the Temple's strong advocacy for Black American Civil Rights. Throughout the events surrounding Leo Frank, Rabbi Marx stood courageously firm in Frank's defense. Leo was exotic and urbane to Lucille. He had traveled to Europe, knew German, Yiddish and even Hebrew. Though born in Texas, he was considered by all a New York Jewish sophisticate. 1912, Atlanta's B'nai Brith Chapter, 500 members strong and the largest in the South, elected Leo Frank its president. Frank, not personally wealthy, worked very hard at the Pencil Factory. He frequently worked on Saturdays, to run the factory profitably and successful for his Uncle and his Uncle's Atlanta business associates. Economic times were hard in the South. Large numbers of rural Georgians were migrating to Atlanta seeking work at minimal wages in the Atlanta factories. Child labor was common.

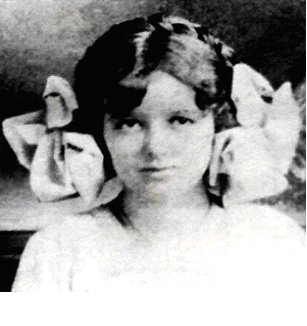

Mary Phagan[2], Murdered April 26, 1913 Saturday, April 26, 1913 was a beautiful day. Mary Phagan, a young 13 year old worker in the National Pencil Factory came into Atlanta to watch the annual Confederate Day parade and celebrations. She was owned $1.20 of back pay from the factory. Her family needed the money. She dressed up in her finery. She took a parasol with her when she left her home in Marietta, Georgia outside of Atlanta in the morning. The factory was closed that day, everyone was at the Confederate celebrations but Mary knew that the superintendent would probably be there working. She would collect her pay from him. Leo Frank did not attend the Confederate Day celebrations. He was upstairs alone in his office working on the company books when Mary arrived about noon. Exactly what happened after Mary arrived was the subject of very heated arguments that could turn violent in Atlanta of 1913. It can today, 100 years later. One fact was never open to argument. Little Mary's body was found at 3:15 a.m., in the basement, by the Black night watchman, Newt Lee. Mary's body had been dumped near an incinerator. Her dress was hiked up around her waist. Her head was bruised and battered. Her bloody underwear, still about her hips, had been ripped open near the vagina. It appeared she had been raped. A seven foot piece of wrapping cord looped and tied about her neck, dug into her flesh so deeply, it confirmed she had been dragged to where Lee found her. Her face and visible body was so blackened from soot, coal dust and ash, Lee, nor the Atlanta police who arrived after Lee failed to reach the Superintendent of the Factory and called them, could tell if she was White or Black. Two "murder notes" were found near Mary's body: "he said he wood love me land down play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his self." "mam that negro hire down here did this, I went to make water and he push me down that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it wase long sleam tall negro I write while play with me." At first the Atlanta police suspicions focused on Lee as the murderer. But police suspicion broadened as they interacted with Leo Frank, his nervous demeanor, the inconsistencies and contradictions from Frank about the events of that day seemed to implicate him. A young work companion of Phagan's, George Epps, came forward and said that Frank had sexually harassed Mary, frightening her. Lee was eventually ruled out as a suspect and another Black employee, Jim Conley, was identified by the Atlanta police as a prime suspect. The police worked on a comprehensive statement from Conley as to what happened. Repeated permutations of Conley's story were given to the police by Conley over hours and days of questioning. Conley directly tied Leo Frank to the murders, yet another iteration of what happened. It was not until May 29, after another new affidavit was satisfactorily extracted from Conley, that the Atlanta police were satisfied. They had incompetently mishandled the physical crime scene for evidence and needed direct testimony to corroborate what became a largely circumstantial case against Leo Frank as the murderer of Mary Phagan. Conley said that Frank used him as a lookout when he had young women come up for his sexual encounters. Conley, in the sworn testimony to the police, said "he had picked up a girl back there and let her fall and that her head hit against something." Together, Conley said he and Frank, took the body to the basement on the factory elevator. Conley then wrote out the "murder notes" in Frank's office. He claimed Frank promised him $200 if he would burn the body. Money he said was never paid. The Atlanta Police arrested Leo Frank for the murder of Mary Phagan. Jim Conley was arrested as an accomplice after the fact for his help in moving the body and initially lying on behalf of Frank. The rape and murder of a white woman, even worse, a White child by a Black, was viewed with particular enmity in the South. The rape and murder of a White Christian girl by a Yankee Jew was novel and instantly raised latent hatred unseen in the American experience of Jews. A Grand Jury indicted Leo Frank for the murder. The Grand Jury had four Atlanta Jews on the panel. The Leo Frank jury would have none. The trial began in Atlanta, July 28. Solicitor General Hugh Dorsey for the prosecution. Noted Georgia attorney, Luther Rosser for the defense. Four weeks later, August 25, Leo Frank was convicted. The prosecution brought in witnesses attesting to Leo Frank's sexual demands and lewd behavior in the factory with female employees to prostitutes claiming he was a regular customer. Physical evidence was limited as the Atlanta Police investigations had corrupted, lost and damaged much that could have proven or disproven Leo Frank's guilt. The Police's examination of the crime scene, seriously tainted by sheer incompetence, compromised, almost completely, what was found and observed there. Witnesses against Frank were intimidated and coached by the prosecutor and police. Jim Conley's testimony was repeatedly rehearsed, perfecting it, by the prosecutor, Hugh Dorsey. Hugh Dorsey would leverage his previously lackluster career, punctuated with repeated prosecutorial failures, to win himself the Governorship of Georgia in 1917. Mary Dorsey was Hugh Dorsey's sister. Mary's daughter married Luther Rosser Jr., the son of Leo Frank's defense attorney. Many witnesses, after the trial, recanted their testimonies against Frank. Even the trial Judge, Judge Leonard Roan, had deep misgivings about the trial and its outcome. He strongly recommended to Governor John Slaton that Slaton should commute the death sentence that Roan himself had ordered. Leo Frank sat calmly and stoically during the trial. He displayed none of the nervous characteristics that the Atlanta Police claimed he demonstrated when he was being investigated. His demeanor was the opposite of what had been portrayed in the papers exorcising the worst of Yellow Journalism. The print media found a goldmine of copy. Extremist, anti-Semitic, populist journalism filled the Atlanta streets from Tom Watson's vicious, hate gorged pages of his newspaper, the "Jeffersonian". Georgia voices were raised against the extremism. They were drowned out. Jews, throughout the South, especially in Georgia and Atlanta, lived in fear. Some chose to relocate for their own safety. They were bewildered, how could such anti-Jewish hatred suddenly emerge in America? Jews had come to America to be free of such virulent hatred. For decades after Leo Frank's lynching, Atlanta Jews spoke only in hushed voices about Frank. The fear of the mob, the hate that was raised, it was all very real and intimidating to them. Huge crowds gathered daily outside of the courtroom. The mood of the crowds was tense, ugly, hostile. They did not hurl anti-Semitic chants or slurs that could be heard in the courtroom proceedings. Murmuring electricity surged amongst them as every turn in the trial was reported. Outbursts, clapping, laughing, did occur from the court room audience as points were being made against Frank. Frank's wife burst out with an epithet against the prosecutor and had to be escorted from the trial with a stern warning. She returned and sat quietly. Good character witnesses came from all over to support Frank. Female factory workers attested that Frank had never sexually intimidated or sexually assaulted any of them. Counter experts contradicted prosecutorial claims. Frank had the finest Georgia lawyers for his defense during the trial. The lawyers proved strangely imprecise, weak, with no insightfulness that was useful. Investigators hired by Frank supporters reported secretly to the prosecution. Key defense evidence was not examined, developed and presented to the jury. What finally convicted Leo Frank of murdering Little Mary Phagan was not the testimonies and statements of the prosecution witnesses who attested to timelines, character and surmised motives. Almost everything that the prosecution presented was circumstantial. The claim that Mary had been raped was contradicted by doctors who could not agree if she was raped or was having her period. The hair found on a lathe, thought to be where Mary had struck her head, could not be authenticated as being Mary's. The physical evidence linking Frank to the murder was at best imprecise and vague. Seventy year after the trial, an old man came out of the shadows. He had been a cleaner in Leo Frank's office the day of the murder. Alonzo Mann came forward with startling testimony about what he saw that terrible day in April in the Pencil Factory. Mann wanted to clear his conscience before man and God. He knew his passing was getting closer from cancer. Mann said he was only fourteen years old when he saw Jim Conley, not Leo Frank, carrying the body of Mary Phagan. He had kept his secret all these years. His testimony, coming when it did outside of cross examination in a court of law, did nothing to save the life of Leo Frank. It did posthumously aide Frank later. One witness that the jury believed could not be shaken. That witness had been cross examined on the stand and his testimony was demonstrated as questionable. The jury refused to not believe the witness. It was common knowledge that a Black testifying against a White man would not be capable of such lies against a White man when pressured. The Black man must be telling the truth. The witness, the prosecutor represented, spoke from first hand involvement in the murder of Mary. It was Jim Conley. The prosecutors asserted that Conley's last and final affidavit was the accurate statement of facts. Jim Conley testified that Leo Frank had lured Mary Phagan to his office and wanted to have his way with her. He killed her when he could not. Conley helped Frank dispose of the body for bribe money. The jury, the prosecution, and the judge believed Jim Conley. The expensive Rosser defense team purchased with "New York Jew money" could not shake Conley enough. Conley had been caught in lies. It was not enough to defeat the meat of Conley's testimony or get a single juror to doubt what he said. Frank was convicted. Judge Roan sentenced Frank to be hung by the State of Georgia. February 24, 1914, Jim Conley was convicted of being an accomplice after the fact in the murder of Mary Phagan. He was sentenced to a year in prison. That same year, October, 1914, Conley's own attorney, William Smith, deeply troubled by what he learned through his association with Jim Conley, said he believed that Jim Conley was guilty of the murder of Mary Phagan. Leo Frank was innocent. Jim Conley periodically turned up involved in various crimes for years after his release from prison in 1915. He would vanish from history. No one knows where. For the next two years, following Leo Frank's conviction, a national campaign to overturn the jury decision was led by Adolph Ochs, publisher of the New York Times and A.D. Lasker. The two men believed that anti-Semitism had convicted Leo Frank. From their New York vantage point they failed to understand the depths of class and regional hatred, vestiges of the Civil War, which permeated the South. Though they raised massive national social support for Leo Frank outside of Georgia, they did just the opposite inside Georgia. Anger built up at the outsiders intent on using their "Jewish money" to besmirch Georgia, denigrating her judicial system, crushing her in a symbolic second burning of Atlanta. Barely fifty years earlier, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman swore to make Georgia howl as his Yankee army burned its way across the state. Georgia populist, and later U.S. Senator, Tom Watson summarized the sentiment in Georgia of the anti-Leo Frank supporters, "Self-appointed elites representing money and privilege had decreed that a child laborer's life was not equal in value to that of a Jewish industrialist." Appeal of the Leo Frank conviction reached the Georgia Supreme Court. It failed. November, 1913, an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, to free Frank, was denied. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote dissentingly of the denial," I very seriously doubt if the petitioner. has had due process of law.because of the trial taking place in the presence of a hostile demonstration and seemingly dangerous crowd, thought by the presiding Judge to be ready for violence unless a verdict of guilty was rendered." A writ of error was obtained, again allowing Frank's lawyers to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. April 19, 1915, the Supreme Court denied the appeal by a vote of 7-2. Again, Justice Holmes dissented and he was joined by Justice Charles Evan Hughes who wrote, "It is our duty.to declare lynch law as little valid when practiced by a regularly drawn jury as when administered by one elected by a mob intent on death."

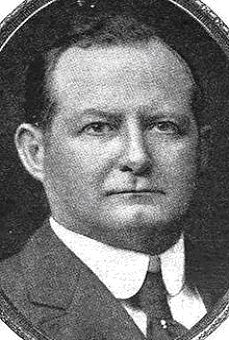

Gov. John M. Slaton The days were drawing closer for Leo Frank's execution. The defense team appealed to the Georgia State Prison Commission to commute Frank's sentence from death to life imprisonment. June 9, 1915, just weeks before Governor John Marshall Slaton's term was to end on June 26, the Georgia State Prison Commission submitted to Governor Slaton a divided opinion, 2-1, in favor of death for Leo Frank. It landed on the Governor's desk for his final disposition. Of all the decisions that Governor Slaton would have to make, he did not want this decision on his desk this late in his term. His chances of ever being elected to the U.S. Senate hung in balance. He could have passed the decision to his successor Governor Harrison. His sense of duty and conscience would not permit him to do that. Slaton decided to consider the commutation request of Leo Frank. His decision would shape his political life or death. It would mean if Leo Frank lived or died. His decision could also mean if Slaton himself lived or died. The issue for Slaton had nothing to do with Frank being Jewish. Slaton's anti-Semitic detractors claimed then and as they still do today, he became involved in the Frank case because his law firm was involved in the Frank defense. One of the partners was Jewish. Slaton, the bigots assert, involved himself because it meant money for his law firm. for him. The truth was that Slaton had no need for money. His wife, Sarah Frances Grant, was the wealthiest woman in Georgia. The reason Slaton decided to consider the Frank commutation was because it had everything to do with justice and the rule of law for all Georgians. Threatened and bribed with a U.S. Senate seat, Slaton refused to back down from his responsibility as Governor. John Marshal Slaton, or Jack as he was known to his friends, was born on Christmas Day, December 25, 1866, in Meriwether County, Georgia. He attended the University of Georgia, graduating in 1886 with high honors and a Master of Arts degree. He chose law as his profession and relocated to Atlanta to practice. He was thirty two years old when he married Sally Frances Grant in 1898. She was his rock of steady conscience throughout their long married life. Slaton's life proceeded, quietly, appropriately, as a patricians life should. He ran for office and was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives from Fulton County, serving from 1896-1909. Popular, respected and capable, he became Speaker of the Georgia House Representatives (1905-1909). Slaton was elected to the Georgia Senate, representing the 35th District, 1909-1913. Two of the years, while serving in the Senate, Slaton was elected President of the Senate, 1909-1911. Because of the death of Governor M. Hoke Smith in 1912, Slaton succeeded Smith as Governor of Georgia for a two month period, November 16, 1911 until January 25, 1912. A year and a half later, Slaton was elected in his own right, Governor of Georgia. It was the biggest landslide victory in Georgia history to date. John M. Slaton became Georgia's 60th Governor. He served from 1913-1915. Slaton's terms as Governor were mundane and easily lost in the fog of history. He modernized Georgia's tax system and roads, reviewed questions requiring executive actions such as appointments and commutations. Slaton would have been an obscure part of Georgia history, perhaps rising to the U.S. Senate as was his expected right. Fate, honor and courage changed everything for Slaton. The sensational murder of Little Mary Phagan had taken place before Slaton officially became Governor. He was well aware of the proceedings and kept his political distance as the Georgia police and legal system proceeded apace. He followed the events of the trial, the appeals and the rising tensions of mob rule, racial hatred and demands for capital punishment that swirled like a gathering cyclone about the country centering on Georgia. Months before the Frank commutation request made it to his desk as Governor, Slaton and his small staff had been preparing their considerations of what would they do if it actually came to him? With little doubt, he would have preferred to have had the decision land on his successor's, Nathaniel Harris, desk. It did not. It came to him.

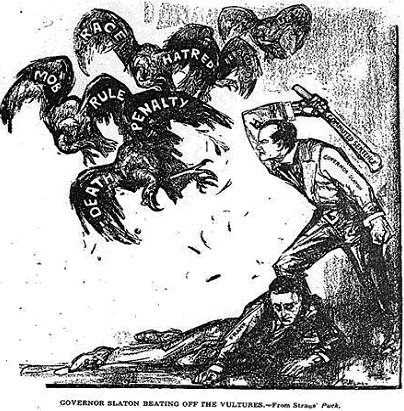

Gov. Slaton beating off the vultures The world had its eyes on Georgia. The world had its eyes on Governor Slaton and so did Americans nationwide. An estimated 100,000 letters poured into the Governor's office demanding that Slaton commute Leo Frank's sentence. With only weeks left in office, Slaton undertook the gargantuan task of reviewing in depth and detail the case of Leo Frank. Slaton laboriously reviewed over 10,000 pages of testimony. He reviewed the events of the trial and the people involved in it. He personally went to the National Pencil Factory to see for himself where the murder was alleged to have occurred and where Mary's body was found. He reviewed studies of the "murder notes" and personally made a shocking discovery about the evidence and course of the trial. The veracity of the prosecution's key witness was essential for the conviction of Leo Frank. Jim Conley had to be absolutely telling the truth about the events that April day in order for Frank to be guilty without even the vaguest shadow of a doubt. Governor Slaton went to the National Pencil Factory and visited the second floor office and work shop area that the murder was alleged to have been committed in. He then took the elevator to the basement as Conley had said he used the elevator to transport the body to the basement. Conley also testified he used the elevator's landing area as the place he preferred to relieve his bowels. He testified, he defecated at the bottom of the elevator shaft the morning of the murder before he and Frank brought Mary's body down to be burned in the incinerator. The police investigation of the crime scene did not include using the elevator at first. The police used the ladder that connected the basement to the first floor. They did note the uncrushed, fresh human excrement on the bottom of the shaft where the elevator would have normally stopped. Later, the police did use the elevator to descend to the basement. The elevator landed with a jarring thud. The smell of freshly crushed human excrement filled their nostrils. The elevator's braking system was poor. It only stopped, every time it was used, when the elevator hit the bottom of the shaft with a jarring thud, crushing into the floor. It was evident that Conley's testimony of having used the elevator with Frank to transport Mary's body to the basement was a lie. Conley's own excrement would have been crushed if he had. Strangely, Frank's defense team did not pick up on this key piece of evidence which notoriously became known as the Shit in the Shaft defense. It was not the first lie that Conley had been caught in. The Shit in the Shaft defense, if it had been focused on by Frank's lawyer, would have been pivotal in discrediting Conley's testimony. Frank's attorney never did use it. Governor Slaton rode the elevator. He experienced the jarring thud of the elevator crushing into the floor to stop. He took his legal obligation to consider the evidence, the trial and the appeal to the Chief Executive Officer of the State of Georgia, very seriously. He clearly understood the "buck stops with him", as President Harry Truman phrased things. The taking of a human life by the State of Georgia was a matter that needed the utmost scrutiny and review. Slaton grew increasingly uneasy with the absolutely guilty verdict of the jury as his investigations continued. With five days left in his term as Governor, with protests and vigils against commutation, Slaton made up his mind. He told his wife Sally his decision late at night before he released it to the public. He told her it could mean the end of his political career. It could mean his life was in danger. She held him tightly and said, she preferred to be the widow of a brave man than the wife of a coward. Governor John Marshall Slaton's commutation was released in the morning.[5] It was 10,000 words long, 29 pages. In detail, the Governor explained his reasons for commuting Leo Frank's death sentence to life imprisonment. Slaton wrote he did not disagree with the verdict of the court that Frank was guilty but he was not absolutely certain. His uncertainty came from a series of problems. "In the Frank case three matters have developed since the trial which did not come before the jury, to wit: the Carter notes, the testimony of Becker, indicating that the death notes were written in the basement, and the testimony of Dr. Harris, that he was under the impression that the hair on the lathe was not that of Mary Phagan, and thus tending to show that the crime was not committed on the floor of Frank's office." He reserved special condemnation for what he recognized as Jim Conley's false testimony. The Governor's written decision continued: ".The evidence might not have changed the verdict, but it might have caused the jury to render a verdict with the recommendation of mercy. In any event, the performance of my duty under the Constitution is a matter of conscience. The responsibility rests where the power is reposed. Judge Roan, with that awful sense of responsibility, which probably came over him as he thought of that Judge before whom he would shortly appear, calls to me from another world to request that I do that which he should have done. I can endure misconstruction, abuse and condemnation, but I cannot stand the constant companionship of an accusing conscience, which would remind me in every thought that I, as Governor of Georgia, failed to do what I thought to be right. There is a territory "beyond a Reasonable doubt and absolute certainty", for which the law provides in allowing life imprisonment instead of execution. This case has been marked by doubt. The trial judge doubted. Two Judges of the Supreme Court of Georgia doubted. Two Judges of the Supreme Court of the United States doubted. One of the three Prison commissioners doubted. In my judgment, by granting a commutation in this case, I am sustaining the jury, the judge, and the appellate tribunals, and at the same time am discharging that duty which is placed on me by the Constitution of the State. Acting, therefore in accordance with what I believe to be my duty under the circumstances of this case, it is ORDERED: That the sentence in the case of Leo M. Frank is commuted from the death penalty to imprisonment for life. This 21st day of June, 1915. John M. Slaton Governor Leo Frank was commuted one day before he was scheduled to be executed. The Governor immediately ordered that Leo Frank be moved to the State prison in a remote part of Georgia, Milledgeville, for his own safety. It was too dangerous in Atlanta for Leo Frank to remain. Riots broke out. Effigies of Governor Slaton were hung and burned as the "king of the Jews". Tom Watson called in his newspaper, the Jeffersonian, for Frank's lynching. "Lynch law is a good sign; it shows that a sense of justice lives among the people." Thousands of angry armed demonstrators filled the woods near Slaton's home outside of Atlanta. The Georgia militia was called out to protect him. Machine guns were set up. Shots were fired in the night. June 26, Governor Nathaniel Harris was sworn into office. As Governor Harris and former Governor John Slaton emerged from the Capital building, a workman attempted to crush Slaton's skull with an iron bar. The quick action of a member of the entourage saved Slaton's life. He and Sally left shortly afterwards for a three month tour of the United States. Outside of Georgia, he was feted as a hero. Slaton returned periodically over the next ten years. It is unclear, but believed, he spent three years in Romania working with the Red Cross during World War I. Slaton eventually did return to Georgia full time. He continued to practice law and even attempted, briefly, to reenter politics. He failed. Near the end of his career, he was honored by his law profession in Georgia and by a small university. He was never honored by the State of Georgia. His name remained that of a pariah to many Georgians who would not simply forget about Leo Frank. Leo Frank was not forgotten. Deep intense anger was retained by many citizens of Georgia who felt that Frank had been given a fair and impartial trial, as best as was possible, in 1913. The trial results were unacceptable to those who hated Georgia, especially the Northern Jewish interests. Leo Frank deserved to die for his crime in their view. Frank had cheated death and justice. Slaton had been bought off. Lynch law was justified. It was commonly used in the South and the West of the United States to bring justice when there was no justice. Slaton had moved Frank to the Georgia State Prison Farm in Milledgeville, for Frank's own safety. While in the Prison Farm, a fellow prisoner, J. William Creen, slashed Frank's throat. Ironically, Frank's life was saved by two inmates, both doctors, who were incarcerated with Frank for their own crimes. In Marietta, Georgia, where Mary Phagan was from and now buried in mournful solemnity by thousands of mourners, a local response to justice unfulfilled arose. The Knights of Mary Phagan was born. They organized themselves along military lines with the intent of kidnapping Leo Frank from the Milledgeville Prison and bringing him to his deserved justice in Marietta. Twenty eight local men, locally well known, were organized. Amongst them was Joseph Mackey Brown, a two term Governor of Georgia, Eugene Herbert Clay, the former Mayor of Marietta and later president of the Georgia Senate, E.P. Dobbs, the presiding mayor of Marietta, Moultrie McKinney Sessions, a lawyer and a banker, several current and former Cobb County sheriffs and other individuals. The enlisted lynch mob included an electrician to cut the lines to the prison, a mechanic for the cars, a locksmith, a telephone man, a medic, a hangman and a lay preacher. With military precision, and little resistance in Milledgeville, Frank was taken from his cell and whisked to Marietta where a rope hanging from a tree awaited him. As Frank's car, with his guards, pulled up to Frey's Gin Road, hundreds of onlookers were already waiting. A Judge of the Cobb County court looked on. A photographer snapped pictures of the event. The pictures were sold for years as souvenirs postcards. Frank was given a moment to say a few words. Protesting his innocence had little effect on the lynch mob. Still in his night shirt, a bandage about his healing throat where the knife blade had recently sliced it open, Frank was lynched. Curious onlookers came up to Frank's hanging body and lifted his night shirt to observe his circumcised penis that they had heard about and was rumored to be "abnormal". Frank's dead body was taken down and placed in the back of a truck to be transported to a funeral home in Atlanta. The embalmed body went on display for thousands who wished to see Frank's body before it was sent to New York for burial. Lucille Frank accompanied the body to New York, much as she stayed closely by his side every moment she could during his trial. Frank was buried in the Mt. Carmel Cemetery in Glendale, New York, in the family plot of the Stern-Frank family.

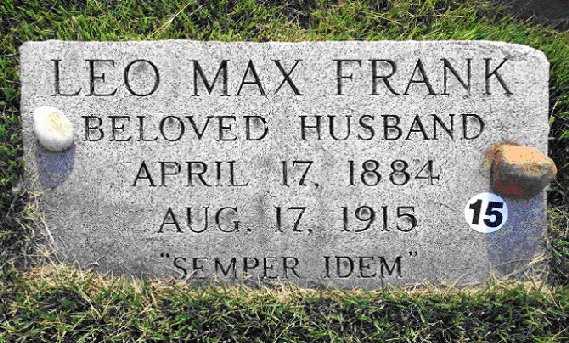

Leo Frank's Grave Site A footstone was added to demarcate Leo Frank's resting place. At the bottom of the footstone two Latin words were added. "Semper Idem" - Always the Same. For most non-Jewish visitors to Frank's gravesite, the words do not make sense. It is because of the context of the meaning. Always the Same - even in America - anti-Semitism means Jewish victimization.

Leo Frank's Grave Stone The lynching of Leo Frank traumatized a generation of Jews. Their belief in America as the "Goldene Medina", the Golden Land, was deeply shaken. Was there justice for the Jew in America, would there be justice for the Jew in America, sits deep within the meaning of Semper Idem. From the fears of Semper Idem rose the American Jewish response, not a religious response but a social response of seeking Justice. If there was no Justice for the oppressed how could there be justice for the Jews?

Stone Mountain[6] From the Leo Frank tragedy, the Ku Klux Klan was reborn on top of Atlanta's Stone Mountain, above the giant carved images of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. By the mid 1920's the preeminent anti-Catholic, anti-Black, anti-Semitic hate group grew to number in the millions. It fell equally fast from internal corruption. The Anti-Defamation League fighting for Justice, for Jewish interests and the interests of oppressed Americans, was born as a direct result of the Leo Frank tragedy. It continues the fight for justice to this day.

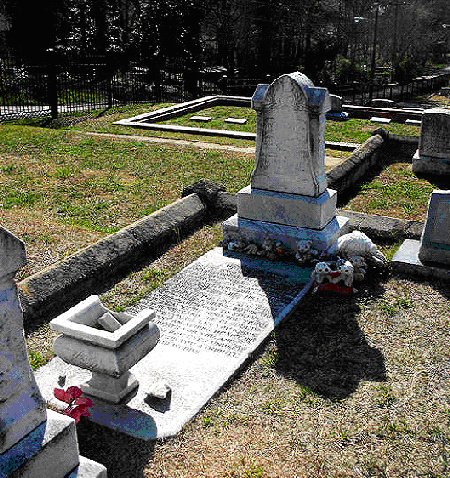

Lucille Frank's Gravesite Lucille Frank never remarried. When she died in 1955, her will specifically expressed that she not be buried in New York next to Leo Frank. She wished to be cremated and have her ashes scattered in Atlanta where she remained all her life. She was cremated. Her ashes were never scattered but quietly buried after years of remaining unwanted in the mortuary, squeezed between her parent's graves in Atlanta. An unknown mourner marked the site of her ashes with an Angel and a small inscription in recent years. "Forever with the Angels, Always in our Hearts."

In 1983, after Alonzo Mann came forward with his revelations about what happened in the Pencil Factory the morning of Mary's murder, a resurgent effort to grant Leo Frank a full pardon began. Led by the Anti-Defamation League's Dale Schwartz, the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles was approached. The effort failed at first but a compromise was finally found that the Prison Commission could go along with three years later. March 11, 1986, a backhanded pardon of Leo Frank was granted. It was not based upon the new evidence but upon how Georgia had failed in her responsibility to handle the safety of Leo Frank. "Without attempting to address the question of guilt or innocence, and in recognition of the State's failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the State's failure to bring his killers to justice, and as an effort to heal old wounds, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, in compliance with its Constitutional and statutory authority, hereby grants to Leo M. Frank a Pardon."

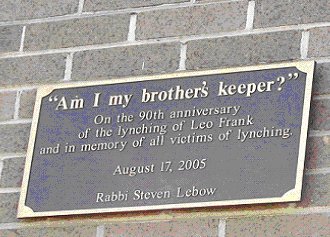

Rabbi Stephen Lebow of Temple Kol Emeth in Marietta, Georgia began a vigil at the site of the Leo Frank lynching in 1995. He has fought for justice for Leo Frank for twenty years. Lebow worked with the owner of the Frank lynching site to place two small memorial markers on the small office building that had been erected there. It was a focal point for an annual memorial service that he and members of the community observed. Beginning in 2004, the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation began an effort to properly mark the site of the Leo Frank lynching historically. It became very important to do so because the building where Rabbi Lebow had placed his small memorial markers was going to be torn down to make room for a highway off ramp. The historical integrity and the historicity of the site of the Leo Frank lynching was going to be lost forever. JASHP had learned, under Georgia law, if a site of significant historical importance is marked with a Georgia Historical Society (GHS) interpretive maker, the historicity of the site must be preserved. Eminent domain cannot be overcome even for history but what JASHP realized was if a GHS marker is located at the lynching site, and the site is redeveloped, the marker must be replaced appropriately, nearby, once construction is completed. In other words, if a GHS marker is erected for Leo Frank, the marker must be put back and the meaning and significance of the site will be preserved for future generations. A four year effort ensued, led by JASHP, and culminated in 2008. In a dedication program sponsored by the Anti-Defamation League, attended by former Georgia Governor Roy Barnes, Rabbi Lebow of Kol Emeth, Jerry Klinger of JASHP, Georgians, Jews and non-Jews, including family descendents of the onetime lynch mob, and political leaders, a Georgia Historical Society interpretive marker was placed at the lynching site. [7] [8]

Marker at Lynching Site The text of the marker reads: "Near this location on August 17, 1915, Leo M. Frank, the Jewish superintendent of the National Pencil Company, in Atlanta, was lynched for the murder of thirteen year old Mary Phagan, a factory employee. A highly controversial trial fueled by societal tensions and anti-Semitism resulted in a guilty verdict in 1913. After Governor John M. Slaton commuted his sentence from death to life in prison, Frank was kidnapped from the state prison at Milledgeville and taken to Phagan's hometown of Marietta where he was hanged before a local crowd. Without addressing guilt or innocence and recognition of the state's failure to protect Frank or bring his killers to justice he was granted a posthumous pardon in 1986.

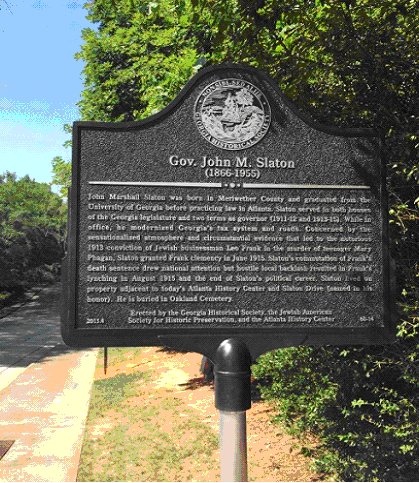

Mary Phagan's gravesite Mary Phagan was an innocent little girl whose life was horribly and tragically taken. Her gravesite in Marietta has become a shrine. Mourners come regularly and leave little offerings of stuffed toys and dolls. Coins are placed on the edges of her grave and in the broken funeral flower urn. Governor John M. Slaton remained a pariah for a hundred years. He was never honored by the State of Georgia. His bravery and appropriate action to commute Leo Frank's death sentence was never recognized or acknowledged by anyone officially.

Governor Slaton historic marker 2013, JASHP began an interchange with the Georgia Historical Society to see about placing a Georgia Historical Society marker honoring Governor John Slaton. With the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation as the lead, support for the effort was enlisted from the Atlanta History Center, Mr. Frank Walsh of Atlanta became a key connection and supporter, Rabbi Stephen Lebow, the Anti-Defamation League, the Georgia Historical Society, Georgia Government officials, Georgians, both Jewish and non-Jewish, members of the Georgia Judiciary, including the Georgia Supreme Court, and members of Governor Slaton's family came together, June 17, 2015. For the first time in Georgia History, Governor John M. Slaton was honored. The text of the marker reads: "Gov. John M. Slaton (1866-1955) John Marshall Slaton was born in Meriwether County and graduated from the University of Georgia before practicing law in Atlanta. Slaton served in both houses of the Georgia legislature and two terms as governor (1911-1912 and 1913-1915). While in office, he modernized Georgia's tax system and roads. Concerned by the sensationalized atmosphere and circumstantial evidence that led to the notorious 1913 conviction of Jewish businessman Leo Frank in the murder of teenager Mary Phagan, Slaton granted Frank clemency in June 1915. Slaton's commutation of Frank's death sentence drew national attention but hostile local backlash resulted in Frank's lynching in August 1915 and the end of Slaton's political career. Slaton lived on property adjacent to today's Atlanta History Center and Slaton Drive (named in his honor). He is buried in Oakland Cemetery. Erected by the Georgia Historical Society, Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, and the Atlanta History Center." Letters of support for the Governor Slaton project were solicited by JASHP and presented by Jerry Klinger at the dedication. Letters of support came from Georgia Governor Nathan Deal[9], U.S. Senator David Perdue[10], U.S. Senator Johnny Isakson[11] and Congressman John Lewis[12] Georgia Supreme Court Justice David Nahmias spoke at the dedication of the Slaton marker: "In the final blot that the case placed on the history of our state, a mob kidnapped Leo Frank, drove him to Marietta, and lynched him. It is altogether right that we still celebrate what Governor Slaton did, because we need to remember those who stood tall in defense of the rule of law, to inspire all of us who need to stand tall when the rule of law is again threatened, as it is in one way or another almost every day. We need to fight for equal justice under the law, even if we do not immediately prevail. Governor Slaton is and should be a particular inspiration to people like me - judges on the courts of Georgia and on the federal courts - the kind of judges who were unable to protect Leo Frank from the unjust ending that the mob demanded. " From the speech of Jerry Klinger at the Slaton marker dedication: 'The words carved into Leo Frank's footstone still ring in people's ears. Semper Idem, Always the same for the Jew. The words have truth in Europe and around the world as anti-Semitism grows in the guise of being anti-Israel. As it was in 1915, the words Semper Idem do not have to mean, always the same, in a negative sense. It must be remembered, it must be acknowledged, that people like Governor John Slaton do exist. There were brave people who were willing to face the mob and racial hatred in 1915. Today, some only see darkness for the Jew, even in America. They should know they are wrong. Semper Idem, there are always people, brave people, people whose hearts are not filled with hate, who are willing to risk it all for justice, toleration and the freedoms that Americans so deeply cherish for a better tomorrow." Jerry Klinger is president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. [1] Latin - Always the Same [2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8sZLBpwviIk [3] http://www.the-temple.org/ [4] http://the-temple.org/AboutUs/History/RabbiDavidMarx.aspx http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/frank/frankclemency.html[5] By Abhijitsathe (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons[6] [7] http://www.jewish-american-society-for-historic-preservation.org/leofrank.html [8] The marker has been temporarily relocated to the Breman Museum in Atlanta for safe keeping until construction of the off ramp is completed. The marker will be appropriately placed near the original site at that time. [9] To: The attendees of the Governor John Slaton Historical Marker Dedication Ceremony Greetings: I am pleased to extend my warmest regards to the Georgia Historical Society, the Atlanta History Center, and the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation as you host the dedication ceremony for Governor John Slaton's historical marker. On behalf of the State of Georgia, it is a pleasure to be part of this historically signify cant event recognizing the late Governor Slaton. Please allow me to welcome today's distinguished guests, relatives of Govern Slaton, and other attendees. Governor Slaton played a vital role in the State of Georgia, first as a member of the Georgia General Assembly and later as the state's 60th governor. He demonstrated a continued commitment to the wellbeing of our state, nation, and his fellow citizens. I applaud those attending today's reception for being a part of this event which celebrates his exceptional life of service and acknowledges his countless contributions to our great state. It is my hope that the memorialization of this marker will afford future generations the opportunity to now of and appreciate govern Slaton and his place in Georgia's history. I commend the various groups and individuals who had a hand in organizing this important event. Sandra and I send our best wishes for a successful and memorable ceremony. Sincerely, Nathan Deal [10] Mr. Jerry Klinger President, JASHP 16405 Equestrian Lane Rockville, Md. 20855 Dear Mr. Klinger It is with great privilege that I join you, the Georgia Historical Society, the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, and the Atlanta History Center in honoring the life and legacy of Governor John Marshall Slaton. As our state's sixtieth governor, Slaton served as a model of unwavering principle. Governor Slaton's conviction for his constitutional duty is a reminder of the solemn dedication by our public officials. His devotion to these principles, over public opinion and at known personal cost, demonstrated extraordinary courage and resolve that serves as an example to all. There is no better tribute to Governor Slaton than by honoring him this month, the 100th anniversary of his courageous decision, with this historical marker. May it serve as a reminder of his significant contributions to our state and inspire future generations to imitate his commitment to the rule of law and justice for all. Kindest regards, David A. Perdue [11] Georgia Historical Society 260 14th Street, Northwest Suite A-148 Atlanta, Georgia 30318 Greetings, It is with great pleasure that I send my heartfelt thanks to the Georgia Historical Society, the Atlanta History Center, and the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation for ensuring that Governor John Slaton's courageous role in Georgia's history is recognized with today's historical marker dedication. I wish you well as you celebrate the placement of this marker. I am proud and grateful that there are organizations such as yours that are dedicated to preserving our state's history and honoring those leaders from whom future generations can learn. With my warmest personal regards, Sincerely, Johnny Isakson [12] Dear Friends: I write to congratulate you on the dedication of the new Georgia Historical Society marker honoring Governor John Slaton. Governor Slaton's role in the Leo Frank case should be an inspiration to all Georgians. Though it cost him his political career, Governor Slaton did the right thing by commuting Leo Frank's sentence. He is one in a long line of Georgians who have stood against the forces of racial prejudice and mob violence. I am proud that he is being recognized today. I hope many visitors to the Atlanta History Center will read this historic marker and learn the importance of courage in the face of discrimination. Keep the faith, John Lewis Member of Congress from the 2015 Editions of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |