|

Acco, Acre and Akko

By Jacqueline Schaalje

Akko does not have any of history's major events; nevertheless, historical

giants such Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Francis of Assisi and Marco

Polo, (who sailed on his journey to the Orient from Acco) visited this

ancient sea-port city.

With so many historic VIPs visiting the town, it's almost as if

something had to happen!

But yes, there was one great event. It changed the course of history. On

his campaign in 1799 to Egypt and Israel, with the intention to storm

onwards to India, Napoleon Bonaparte laid siege to Acco. He failed

miserably. He never reached India, and India never became a French colony

but was instead conquered by the English. Napoleon had to pull back to

Egypt, and from there took a ship back to Paris.

In fact Napoleon's army had suffered such a tremendous defeat, pared with a shortage of transport for the many wounded and sick under his men, that they were barely able to make a retreat at all. Before the march back to Egypt, therefore, Napoleon decided to shed some empty weight. The French army buried their equipment on the shore of Acco. Napoleon sent some of his siege equipment on leaky flotillas out into open sea. To this day arms and other reminders of Napoleon's stay in Acco, for instance bullets, guns, pieces of cannon etc, are washed up or are dug up on the beach.

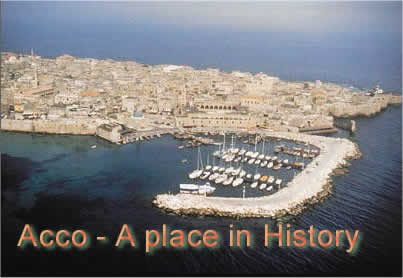

It still seems a marvel that Acco held the great French commander in check. Acco, a quiet and friendly city stuck away in the North of Israel, is surrounded by the sea on three quarters of its sides. Its great walls, rebuilt by the city's defender against Napoleon, Pasha el-Djezzar, still loom impenetrable.

Today mainly Arabs live in the old city centre, and are peacefully cohabiting with Jewish residents in the newer neighbourhoods; not an easy feat in these days.

Although many peoples conquered it, Acco was never inhabited by the ancient Israelites. Nor did Jewish people live there until recent times. Acco today remains slightly apart from other cities in Israel. The difference can be explained by its location on the coast.

The city is very old. During biblical times the city was under Canaanite control. It is mentioned in ancient Egyptian scrolls from around 1800 BCE. The city assumed great importance on the trade route between Egypt and Syria. In the Greek era it was called Ptolemais, but after that became known again by its antique name of Acco.

It became the singular most important harbour and trade city in the Levant. It was only eclipsed by the flowering of Caesarea during Roman times. However the artificial harbour of Caesarea silted up with mud after the Arab conquest in the 7th Century. Ibn Tulun made some developments in the port facilities of Acco, and the city and its harbour prospered once more.

After the Crusaders wrested Acco from the Arabs they completely redesigned the town and made it three times as large as the modern walled city's centre. They enclosed the new area in huge walls with towers and a moat. It is the original Crusader design of Acco which is still visible today and accounts for its Medieval appearance of low houses and narrow streets; even though most of the walls and buildings have been reconstructed by the Turks.

A Golden Age began for Acco. From this time stem the Knight's Halls, and another Crusader fortress on the coast. The city continued to be a great trading town, and shops and warehouses thrived on every corner. With 40,000 inhabitants it was quite a large metropolis. But through foreign influences (from the Italian trading cities like Venice, Pisa and Genoa who set up businesses in Acco) the local government crumbled.

Following the defeat of the Crusaders, the city went back into Arab hands again for a few years. The Crusaders did not succeed to enter the defences round the city which they themselves had built, until Richard the Lion-Heart and Philip of France arrived on the scene in 1191 and installed the Latin kingdom which ruled 100 years. As Jerusalem temporarily stayed under Muslim rule, Acco became capital of the Crusader Kingdom in Israel.

The Crusader kingdom succumbed to the Mamluk conquest at the end of the 13th Century. The city lay in ruins until local sheiks established independent city-states. Napoleon's opponent el-Jezzar was one of them. Only after the English took over in Palestine, did Acco reassume its traditional role as harbour for exporting grain from the Golan.

El-Jezzar built the present broad wall around Acco which included relaying the old walls along the sea. Two parts of the wall are originally Crusader: the Land Gate in the east of the old city and the Sea Gate (which is now a part of the picturesque Abu Christo cafe).

A little bit more inside the city near Wiezman Street, lies a second wall which is from the original Crusader wall from the 12th Century. The Crusaders also redesigned the harbour, providing an inner and outer harbour. The city wall stretched southward into the sea as a breakwater, up till the small island, called the Tower of Flies, which used to be a lighthouse.

In the city centre, the great mosque is distinctive. It was built by el-Jezzar in 1781. His and his son's tombs are placed in the courtyard. The marble columns in the courtyard were looted from Caesarea. A visit to the vaults under the mosque is a spooky experience. Stairs lead down there from the courtyard. The huge cellars form the basement of what was once a Crusader church.

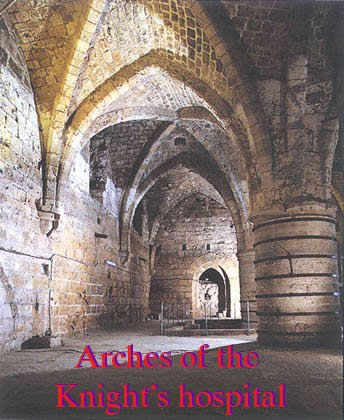

The Crusader city was some 7-8 meters lower than the current city. The crusader fortress, belonging to the Knights of the Hospital, lies below street level; the entrance is opposite the mosque. The actual building used to be a ruin, which was erected again by the Turks. The Knights's halls are reached by passing a Turkish gate. Only three of the seven halls are open to the public. Each hall belonged to a nationality representing the Hospitallers.

The Halls are believed to be the barracks of the Knights, who together with the other knightly orders in Acco were responsible for the defence of the Latin Kingdom. The Crusader Knights were fighters and monks at the same time, and had very strict moral codes and they could not marry.

Opposite the halls are what were possibly the dormitory and the cloister of the Knights. Next to the cloister lies the dining hall, whose walls have fleur-de-lis decorations in Gothic style carved in the stones.

A pit in the centre of the hall gives access to an underground passage. It was discovered by the Crusaders while they were building the dining hall, and they probably maintained it for its secretive value. The ends of the tunnel have not yet been excavated.

Archaeologists have made an exit from the tunnel to what was perhaps the hospital of the knights. The northern entrance to the second story is from the 11th Century and very well preserved. On top of the pillared hospital the castle may have stood. This is gathered from contemporary illustrations.

Other parts in the old city have kept Crusader outlines. For instance the south-west corner used to be the area of the Temple, another order of Knights. The church of St John is built on top of the Crusader church. The Knight's fortress, which was famed for its beauty and strength, must have stood where the sea borders the town. Not a stone remains from it, it was destroyed by the conquest of the Mamluks.

The south-eastern corner of the city's centre formed the Pisan quarter. Here lies the Inn of the Pisans. The other Italian quarters were in the same area. Some Crusader houses may be found in a street a bit further to the North, leading to a square which follows the original Medieval outlines.

The rest of the streets and buildings are from later dates. For instance the Turkish bath built by el-Jezzar next to the Knight's Hospital is a shining example. Prominent are the Khans (Inns), built in a square around a central courtyard, which were used as a meeting place for traders traveling on camels transporting goods and for loading and unloading.

The nicest one of these, Khan el-Umdan (Inn of the Columns), in the south-east corner of the city's centre, has a square clock-tower over the entrance. The tower is from 1906 and newer than the rest of the building which is from or just before el-Jezzar's time. This Khan belonged to the Genoese merchant community, the biggest one in the city.

There are two other Khans, more north in the city. The Khan esh-Shawarda, served for bringing grain from the Golan to the ships in the port. The tower in the south-east corner is from the 13th Century and built by the Crusaders. Religious symbols are visible on the stones. The second Inn, the Khan el-Faranj, means Khan of the Franks, because French merchants established themselves in Acco in the 16th Century.

A visit to old Acco is wonderful way to see and feel the history of the Land of Israel.

from the March 2000 High holiday Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|