|

Ein Gedi

by Jacqueline Schaalje

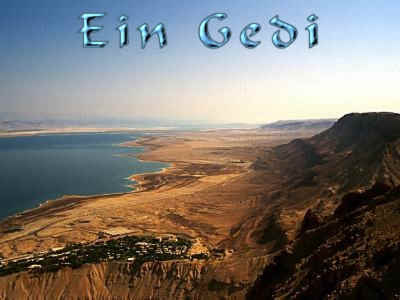

Ein Gedi is a water-resonant oasis on the Dead Sea, and around the early summer is still comfortable to a visit. The Dead Sea area is interesting for the study of the history of Judaism, as its rock caves gave refuge to heroes and ascetics.

Ein Gedi means the Spring of the Kid. This refers to the ibexes, which can be spotted during quiet walks or at the end of afternoons when they descend the mountain to drink in the wadi.(valley)

The history of Ein Gedi starts in the Bible, when it is mentioned several times. The Song of Songs extols its vineyards in "a cluster of henna in the vineyards of Ein Gedi (1:14)" King David hid in the "strongholds of Ein Gedi" after he fled from King Saul (Samuel I, 24:1).

Settlement in Ein Gedi began well before the time of King David. The first inhabitants lived there in the Stone Age (approximately 5000 years ago), but they did not live in the same place as the later habitants or even the present kibbutz of Ein Gedi, but higher up the mountain. The reason for this is that it is near the Ein Gedi spring. After the Stone Age period, Ein Gedi was deserted.

It is mentioned in Bible texts in reference to the Jewish kings. The Davidic strongholds mentioned above have not been found so far. The first Israelite settlement dates from the 7th century, during the time of the kings of Judah, to whose constituency Ein Gedi belonged. According to the second book of Chronicles, King Uzziah built towers and hewing cisterns in the desert; this could be Ein Gedi, although the place is unspecified.

During this time the settlement was moved lower to Tel Goren. The Israelites were the first to use the spring water for irrigation. They built water installations, which led water from the spring to the village. A time of agricultural prosperity began. Ein Gedi became famous for its dates: in Chronicles II, 20:2 it is called "Hazazon-Tamar," tamar being the Hebrew word for date.

A mysterious plant, the persimmon, of which the exact present-day equivalent is not known, grew in Ein Gedi in thick groves. The resin flowing from the plant was collected and produced a most famous perfume. The Israelite kings also extracted perfume for oil from the Ein Gedi groves. King Josiah of Judah installed the practice of anointing new kings with persimmon oil.

The Israelite settlement was destroyed by the Babylonians. Afterwards the settlement was inhabited by returned Jews from Babylon. The settlement thrived during the Hellenistic period.

During the Hasmonean period the agricultural development reached its peak. Even the modern kibbutz of Ein Gedi cultivated less than half the area of land compared to ancient times. Besides dates, tropical and medicinal plants were grown, for instance henna: "My love is a cluster of henna flowers among the vines of Ein Gedi" (Song of Songs 1:14). The yearlong flow of water and abundant sunshine made for good harvests.

The settlement of Ein Gedi itself was fortified during the Hasmonean kings, and crowned with a royal estate. Before the destruction of the Second Temple the Dead Sea area buzzed with religious activity. The sect of Essenes, whose main center was in Qumran, also settled in Ein Gedi in the first century, according to the Roman historian Pliny the Elder. They lived higher up in the mountains, near to the Ein Gedi spring, where archaeologists found remains of 30 living quarters and a water pool.

Meanwhile the Romans had heard about the lucrative perfume business in Ein Gedi. Marc Anthony, the lover of the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, confiscated the persimmon groves for her, but after her death king Herod leased them back. During the First Jewish War, the Jewish inhabitants of Ein Gedi tried to uproot the groves so they would not fall in Roman hands; the Romans fought to prevent it.

A few years before the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, according to the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, fanatic Zealots from Massada invaded the agricultural settlement of Ein Gedi. They stole all of the crops after killing 700 women and children, and returned with the spoils to their stronghold on Massada (War 4:401-4). After it was conquered by the Romans, Ein Gedi became quiet again, due to a Roman unit which enforced peace in the region. The soldiers also built a bathhouse.

During the Second Jewish War (130-135 CE), the famed leader of the Jewish rebels, Bar Kokhba, used Ein Gedi as his main administrative center. At the approach of the Romans he retreated to caves in the area. Once, while cooped up in the cave, he sent the inhabitants of the town a complaint that he did not get enough supplies: "From Shimeon bar Kosiba to the men of Ein Gedi, to Masabala and Yehonathan bar Beayan, Shalom. In comfort you sit, eat and drink from the property of the House of Israel, and care nothing for your brothers." In another letter, the rebel leader makes specific requests in order to celebrate the holiday of Sukkot: they are to pack two donkeys with palm branches (lulavs) and citrons (etrogs), myrtle and willows.

These letters and other artifacts from Bar Kokhba and his fighters, even leather sandals and reed items,are remarkably well preserved because of the dry desert climate. They can be seen in the Israel Museum, in the lower room of the Shrine of the Book.

The Bar Kokhba's resistance did succeed. The Romans took over in Ein Gedi and in all of Israel. Ein Gedi was destroyed once more.

In the third century, Jewish settlers returned to the spot and built a small village. In its midst was one of the earliest synagogues in Israel. Apparently the inhabitants were rich, because they devoted considerable resources to its design. It could be that its wealth was related to the persimmon perfume, but perhaps also came from Dead Sea minerals.

The Jewish settlement was again destroyed, this time by a fire, in the sixth century. It was abandoned until the Mamelukes (13th-14th century) built a small village. They constructed a flourmill that operated by waterpower from the spring. The village was again abandoned soon after, and served as a Bedouin winter location from the 19th century. In the fifties of the last century, the kibbutz movement established a kibbutz, followed by a Field School. The area around it was turned into a nature reserve.

Visit

The archaeological sites of Ein Gedi lie a bit scattered, and good shoes are necessary for climbing. To reach the spring and Stone Age temple, enter Wadi David. After passing the first smaller waterfalls, take a left on a path that points to the Ein Gedi spring, then turn right up a steep path. In the shade of trees, the Shulamit spring flows from a rock on the left. A little bit onwards the picturesque Ein Gedi spring is reached, amidst thorny bushes.

Further up the mountain, a sign points to the temple on a crowning peek. The temple, of which only the first rows of mud brick stones still remain, exists of an open space and two smaller rooms. It was in use around 3000 BCE. As there are no traces of other settlement around, archaeologists usually conclude that it served as a regional sanctuary. This seems to make sense because 6 kilometers southwards cultic objects were found which probably belonged to the temple. The hoard of 416 objects is known as the Treasure Cave of Wadi Mishmar. The objects were dated to the same period. The very beautiful and unique copper crowns, maces and wands decorated with figures of animals are on display in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. To what purpose they were used is not known, although some suggest that the temple celebrated a water cult.

The largest rectangle room of the temple has an altar. Under it a thick layer of ash contained animal bones and small manmade figurines. Animal offerings were found buried in small pits on both ends of the room.

For people with lots of energy, there is a black trail leading up to the top of the cliff. The Romans fortified this path by sustaining walls. On the cliff's edge stand the remains of an Israelite fort, dated to the 7th century BCE. A few hundred meters to the west is a Roman fort. From the forts one glimpses a magnificent view over the Judean desert and on the other sid, on Dead Sea.

Down again, there is a trail leading down to Tel Goren and the synagogue, or alternatively it can be reached by car. Tel Goren, the site of the Israelite, Persian and Hasmonean towns, was dug out, whereby many artifacts came to light such as inscribed seals and silvers coins. Tel Goren was later occupied by the Romans. The Roman bathhouse still remains. It was in this long narrow building that Jewish rebel leader Bar Kokhba administrated his rebellion.

The highpoint of the archaeology in Ein Gedi is the synagogue. The site has only been opened since 1997, after the mosaic floor was accidentally discovered in1965 when the field was plowed. The mosaics have been restored.

Surrounding the synagogue is a labyrinth of small dwellings. Through them, leading to the synagogue the park organization set out a rather irritating pair of routes. The area is actually so small that it is difficult to miss anything just by wandering round. The houses have no special features, except for two ritual baths (mikves).

The synagogue itself dates to the end of the 3rd century CE (Talmudic age), and was renovated by Ein Gedi inhabitants in the 4th century and again, reaching its present form, in the 5th century. The north wall, which is also the wall where the bemah or platform is situated, has two entrances. These are facing Jerusalem.

The left rectangular section presents the newest phase of the building. It has only a basin for washing hands.

The long aisle next to it contains the dedication mosaic. The first eight lines are in Hebrew, and the rest is in Aramaic, the common language during this time. The inscription mentions the patriarchs, the signs of the zodiac, the months of the year; the pillars of the world, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Then it says Peace unto Israel (this inscription is also found in the synagogue in Jericho). Then some local residents were given recognition, called the sons of Hilfi. A Rabbi Yose the son of Hilfi is also commemorated and thanked at the end of the inscription, together with Yonathan the hazan (cantor) and citizens who helped paying for the renovation of the synagogue.

Just before the end there is a mysterious warning:

"Anyone causing a controversy between a man and his friend or whoever slanders his friend before the Gentiles, or whoever steals the property of his friend, or whoever reveals the secret of the town to the Gentiles - He whose eyes range through the whole earth and who sees hidden things, he will set his face on that man and on his seed and will uproot him from under the heavens. […] amen and amen selah."

It has been suggested that this 'secret' refers to the making of perfume from persimmon.

The central prayer hall has a square of stumps belonging to columns that supported the roof. Against the south wall there are benches for the public. The mosaic has a leaf pattern. The central medallion is in the form of a diamond. In the corners a pair of peacocks holds a bunch of grapes in its beak. Encircling the diamond the signs of the zodiac are inscribed. The absence of human forms in the synagogue shows that the community apparently kept to the second commandment.

Near to the north wall a repository was excavated, where sacred writings, scrolls, coins, a bronze cup and a menorah were found. A smaller bird mosaic marks the location of the wooden bemah. Next to it is a stepped seat, called the seat of Moses. It was reserved for the community leader. Two hundred meters from the ticket office there is a Roman cistern, one of fifteen in the reserve.

An impression of what it was like for the Jewish rebels under Bar Kokhba to have lived in desert caves, can be obtained by a walk through Wadi Arugot, also in the reserve but with a separate entrance more to the south. Bar Kokhba's correspondence was found in the Cave of the Letters in Nahal Hever. Nahal Arugot was the route the Romans used to reach Nahal Hever and where they also set up camps.

~~~~~~~

from the April 2002 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|