|

The Division Street Princess

By Elaine M. Soloway

He kept it folded into a square, tight, so it could fit in his wallet.

"My princess wrote it," Daddy says as he pulls a customer by the elbow. He is unfolding the poem I brought home from fourth grade, handing it to Mrs. Lieberman. An "E" for Excellent, bright red ink in the corner of the paper. It's the poem I wrote about my brother Ronnie.

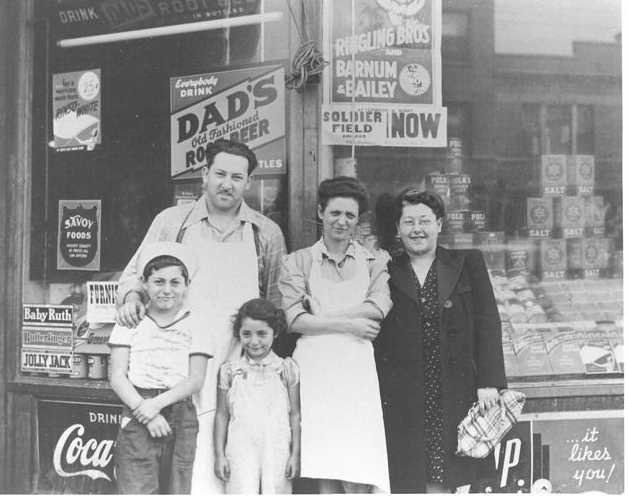

The year is 1948, I am 10 and we are in Irv's Finer Foods, the corner grocery store my parents own on Division Street in Chicago's Humboldt Park neighborhood.

When Daddy goes into his "proud poppa" routine, I tuck myself into a corner of my part of the store. My father has designated some 100 square feet near the front windows as my store. Pretending to straighten the shelf of sundries I've stocked: toothpaste, aspirins, cotton balls; but in truth, I'm eavesdropping. Daddy's words pump up my small-for-my-age body. Inches build as I hear: "See how smart. Look at that E. My princess is a writer."

Over the years, long after my dad has died, whenever confidence flags, I unpack those words, dust them off, and use them once more for support.

Like Dad's words that return to me with pleasure, I see my tiny store and remember how proud I felt in that makeshift space. Dad even gave me my own cash register to use when I waited on customers. It was a cigar box he painted white.

Nothing like the majestic gold-plated one with fat keys and an exploding cash drawer my mom used, but mine nonetheless. This is where I placed the pennies, nickels and dimes that customers handed to me and I returned to them as I counted out change.

Our customers were neighbors-- Jews, Poles, Italians, mostly immigrants from the old country. When Dad stops them to show my poem, they say: "It's lovely, Irv." What else can they say? Irv is a big guy. Not tall. Short in fact, only about five foot four. But he is stocky, broad-shouldered. Muscular arms from swimming at the Y and lifting cartons of canned goods to the shelves. Handsome and well-built at age 38. Overweight and diabetic by the time he dies of a heart attack at 48.

As I look back on the years we owned the store, I think one reason Dad loved my poem so much was because it was about my brother who is three years older than me. Dad was happy his kids cared about each other. Family was important to him. He was from a family of six children, my mother a family of eight. Many aunts, uncles and cousins lived nearby in our poor neighborhood. I felt secure having so many familiar faces around. And despite the hard times, no one went hungry: we had the store, Uncle Morrie had a butcher shop, Uncle Jack a fruit wagon, and Zadie (grandfather), a fish market.

Both of my parents were born in Russia. When they came to this country as young children, anyone old enough to work skipped school to help support the brood. My dad, smart as a professor, never went to high school, let alone college.

I imagine Dad also prized my poem because he was a reader, a lover of words. When he wasn't working in the store, standing behind the butcher counter with his blood-stained apron tied around his belly, or delivering wooden crates of pop bottles to customers up and down the block, Dad was reading. Mickey Spillane, crime stories, paperbacks. Books all over the house.

When we owned the store, our family lived upstairs in a three-room flat above Irv's Finer Foods. After work, Dad would sit in a favorite armchair worn flat by his growing weight, the fabric studded with cigarette burns. His small feet resting on a hassock. On the table nearby was an ashtray with half a dozen butts and one lit Camel, its filterless tip growing whiter as Dad escaped Division street, the store, and Mom's pleas to stop eating. An opened paperback flat against his stomach, belt and top pants button undone, Dad fast asleep and snoring. Maybe dreaming of crime solving. At his elbow, a large pitcher of water. Thirsty from the diabetes already damaging his young body.

I knew Dad was in danger -- his doctors warned him often -- but I also knew he could not help himself. "It's no life if I have to diet," he would say.

I sympathized with him then, took his side against Mom's nags, but today, with daughters he never got to meet, or new triumphs he missed sharing, I'm angry. "For me, Dad," I think, "couldn't you have done it for me."

I was in a college classroom when the news came. "You're wanted at the hospital," my professor whispered in my ear. He had just taken a message from someone who tiptoed into the room. I raced down the marble steps, crying as I opened the door to a cab. I knew what awaited me.

A previous heart attack, the raging diabetes that had almost cost him a leg, the three packs a day of Camels, and his appetite for food -- all would gather now for their final blow.

When Mom and I took home his personal affects -- eyeglasses, keys, wallet -- I looked to see if it was still there. My poem about Ronnie, the lined notebook paper brown with fingerprints and barely attached at the folds, the blue inked words faded, hardly legible. With him to the end. With me forever after.

~~~~~~~

from the March 2003 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|